Spanking and Child Behavior Problems

6 The Boomerang Effect of Spanking

Public approval of spanking has declined drastically in the past generation. Actual use of corporal punishment (spanking) on older children has dropped by about half since 1975 (see Chapter 17). Despite this, spanking remains an almost universal experience of children in the United States because, as was shown in Chapter 2 on spanking in the United States, at least 94% of parents spank and slap toddlers. Because every child was a toddler, this means that being hit by parents at least occasionally is an almost universal part of growing up in an American family. The 94% rate also suggests that parents are either not aware of, or choose to ignore, the possible harmful side effects of slapping and spanking. Surveys of pediatricians, psychologists, and sociologists have found that they also seem to give little attention to the possible harmful side effects of spanking. A clear indication is the virtual omission of spanking in child development textbooks shown in Chapter 1 and the surveys of pediatricians and psychologists (Anderson & Anderson, 1976; Schenck et al., 2000; White, 1993). Ignoring the harmful side effects of spanking flies in the face of a large and highly consistent body of research indicating that spanking is associated with an increased probability of physical aggression and other antisocial behaviors. Gershoff's meta-analysis documents the results of 27 studies of the relationship of corporal punishment to aggression by children (Gershoff, 2002). All27 found that corporal punishment was associated with an increased probability of aggression. Since then, all studies conducted on this relationship have found that spanking is associated with an increased probability of aggression and antisocial behavior.

There are many reasons this evidence has been ignored. One of the most important is the belief that spanking is more effective than nonviolent discipline and is, therefore, sometimes necessary, despite the risk of harmful side effects. The sometimes refers to occasions when a child engages in repeated misbehavior, dangerous behavior such running out into the street, or morally offensive behavior such as hitting other children. These situations occur in the lives of almost all children and that is why, as will be explained more fully in the chapter on why parents are driven to spank (Chapter 18), the belief that spanking is sometimes necessary means that almost all children will be hit by parents.

David B. Sugarman and Jean Giles-Sims are coauthors of this chapter.

As we pointed out in Chapter 3 on spanking throughout the world and in Chapter 4 on the relationship between family size and spanking, the child's behavior is only part of the explanation for spanking. As we previously suggested the evidence on harmful side effects has probably also been ignored because of the belief that spanking is more effective than other modes of correction. Spanking is widely believed to teach a lesson that children will not forget. The results of the study described in this chapter confmn that belief, but in a way that parents do not envision. In fact, they show that the lesson is often the opposite of what parents have in mind when they say, "I don't like to spank, but I had to teach him a lesson."

The specific questions to be addressed in this chapter are:

* What type of study could provide evidence that spanking causes antisocial behavior? This is an important question because, although many studies have found a correlation, a correlation does not provide evidence that there is a causal relationship.

* Does the relation of spanking to antisocial behavior apply to toddlers as well as older children? This is an important question because some argue that it has no harmful effects at early ages (Friedman & Schonberg, 1996a).

* Does the context in which spanking occurs make a difference? This is an important question because it is widely believed that if parents spank in the context of a warm and supportive relationship or that if spanking occurs within a culture where it is the prescriptive or statistical norm, it will not have adverse side effects.

* If parents spank only rarely, will it still cause harm? This question is important because many argue that the rare and judicious use of spanking could have beneficial outcomes.

Spanking and Behavior Problems

There are theoretical reasons to think that the link between spanking and an increased probability of physical aggression by the child is strengthened because parents use spanking for the socially approved and moral purpose of correcting behavior-and because spanking itself is socially approved and viewed as morally correct. Therefore, we could predict that when parents, albeit unintentionally, teach that it is morally appropriate to hit to correct misbehavior, their children will learn to hit others to correct their behavior. Children are continuously faced with situations in which other children are doing something they consider seriously wrong and who persist in that behavior, such as "he squirted water at me and wouldn't stop," "she took all the dolls and won't give me even one," or, later in life, "he made a pass at my girl." If children have learned that it is socially and morally appropriate for parents to hit others to change their behavior, they are more likely to hit others themselves. This is one of the reasons why study after study has found that the more spanking a child experiences, the more likely that child is to hit another child. In addition, other processes, such as those investigated in Chapter 12 examining the link between being spanked and partner violence in adulthood, contribute to the criminogenic nature of spanking.

The adverse effects of spanking have been observed as early as the beginning of the second year oflife. For example, Power and Chapieski (1986) found that toddlers whose mothers frequently spanked had a 58% higher rate of noncompliance with mothers' requests than did children whose parents rarely or never spanked. Among kindergarten children, Strassberg, Dodge, Pettit, and Bates (1994) found that those who were spanked that year had double the rate of hitting other children in school. Using children of widely varying ages, Straus (2001a, Chart 7.1) found that children in the National Family Violence Survey who experienced frequent spanking were twice as likely to severely assault a sibling as children of the same age who were not spanked that year. Analysis of another national survey found that, compared with children who were not spanked, those who were spanked the most were four times as likely to be delinquent (Straus, 2001b). Moreover, Chapter 12 on spanking and partner violence shows that the parents in that study who recalled having experienced corporal punishment during their early teens (about one half of the sample), were three times more likely to have hit their spouse during the previous 12 months.

Which is Cause and Which is Effect?

All of the studies just cited, however, used a research method that can only show that spanking is correlated with behavioral or emotional problems of children. These studies could not show that spanking causes those problems. It is just as plausible that the child's behavior problems caused the spanking. Our perspective is that there is a two-way causal process. This means that, although misbehavior causes spanking, when parents spank to correct misbehavior, it has the long-term effect of increasing the probability of aggression, noncompliance, and, as will be shown in Part IV, delinquency and, later in life, marital violence and other crime. Establishing whether this proposed boomerang effect is correct requires either experimental or longitudinal research that examines change in antisocial behavior subsequent to the spanking. The few longitudinal studies that had been completed prior to the study in this chapter did not measure change in children's behavior subsequent to spanking, so they did not permit inferring a cause-effect relationship (e.g., Simons, Burt, & Simons, 2008; Simons, Johnson, & Conger, 1994). Others, (e.g., Eron, Huesmann, & Zelli, 1991) included spanking in a scale measuring harsh disciplinary practices and therefore could not examine the effect of spanking per se. This problem continues to exist in many studies (e.g., Bender et al., 2007; Ehrensaft et al., 2003) that investigate spanking, but only as part of a harsh discipline scale.

Ethical and practical issues make it impossible to conduct experiments that randomly assign children to spanking or to non-spanking parents. However, longitudinal studies can follow children over time in their natural environments to see what happens in the months and years after they experience spanking. Such studies can provide information about the effects of spanking, but only if the study measures change in behavior-that is, in the months and years subsequent to the spanking, did the child's behavior improve or get worse? Unfortunately, none of the longitudinal studies conducted up to 1997 measured change in children's behavior. Without such a control, even longitudinal studies that follow children for several years are unable to determine which is the cause and which is the effect. When a study fmds that the more spanking a child experienced at Time 1, the more aggressive the child is at Time 2, this could reflect a situation in which parents were responding to a high level of aggression at Time 1. Because aggression is a relatively stable trait, it would not be surprising to find that the most aggressive children at Time 1 were still the most aggressive at Time 2. The most one can conclude from longitudinal studies that do not measure change in children's aggression is that the spanking did not reduce the level ofthat aggression.

The study in this chapter permitted us to overcome the causal direction problem because antisocial behavior was measured at the start of the study and then again two and four years later. This allowed us to determine whether spanking 'resulted in less, or more, antisocial behavior two years later. We tested tpe hypothesis that the more parents spanked at Time I, the greater the increase in children :S antisocial behavior from Time I to Time 2.

Sample and Measures

Sample

The sample consisted of the 807 children of women who were first interviewed in 1979 as part of the National Longitudinal Survey ofYouth who were 6 to 9 years old when their level of antisocial behavior was measured. The data that is reported here was collected in three different waves, two years apart, which enabled us to examine the potential impact of spanking on antisocial behavior over time. For information on the sample and data see Giles-Sims (Baker, Keck, Mott, & Quinlan, 1993; Giles-Sims et al., 1995; Straus, Sugarman, & Giles-Sims, 1997).

The information on spanking was obtained from observation by the interviewer of whether the mother hit the child during the course of the interview and from asking, "Did you find it necessary to spank your child in the past week?" Mothers who said they had spanked were asked: "About how many times, if any, have you had to spank your child in the past week?" We used these data to create a spanking scale that combined the observed and the interview measures. If the mother was observed hitting the child, it was counted as one instance of spanking and this was added to the number of times the mother reported spanking in the previous week. From this scale, we formed four categories of children: those who experienced no spanking (during the interview or the previous week) and those who experienced one, two, or three or more instances of being spanked.

Antisocial Behavior

The measure of child antisocial behavior consists of the following six behaviors: cheats or tells lies, bullies or is cruel or mean to others, does not feel sorry after misbehaving, breaks things deliberately, is disobedient at school, and has trouble getting along with teachers. The mothers were asked if, during the preceding three months, each of the behaviors was not true ofthat child (scored as 1), sometimes true (scored 2), and often true, (scored 3). The antisocial behavior score is the sum of the scores for these behaviors.

Three Other Methodological Problems

In addition to research that does not permit inferring whether spanking causes antisocial behavior, much of the existing research also fails to deal with one or more of three other methodological problems, each of which could undermine the validity of the results.

Overlap with other parental behaviors. What seems to be an effect of spanking could be a spurious relationship. A spurious relation is one that results from some other variable being the underlying cause. For example, if parents who spank also are harsh and rejecting, and lack warmth and affection, those characteristics rather than spanking itself, could be what explains the correlation of spanking with antisocial behavior. Many studies show that harsh and rejecting parents do tend to spank more (Herzberger, 1990; Pinto, Folkers, & Sines, 1991; Simons et al., 1994). However, parents who spank are not usually harsh and rejecting in other ways. Spanking is something done by good parents in the belief that it is necessary to correct misbehavior. Moreover, if parents who spank are harsh and rejecting, because over 94% spank toddlers, it would mean that over 94% of American parents are harsh and rejecting. That is very unlikely. Therefore, it is also unlikely that the harmful side effects of spanking are the result of these other parental behaviors rather than the result of spanking itself Still, it is very important to analyze spanking within the context of parents' child rearing styles. This means that research must separate the effects of spanking from the effects of other parental behaviors. Two crucial aspects of parenting that have been identified in previous research are warmth and cognitive stimulation, which refers to interacting with the child in a way that encourages the child to think and understand (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Emotional support is especially important to take into consideration because it is widely believed that, if spanking is done by parents who provide emotional support, use of spanking in moderation and as a backup rather than a first resort, is beneficial to children (Baumrind et al., 2002). To deal with this problem, the statistical analysis for this study took into account the level of emotional support and cognitive stimulation.

Overlap with sex of child and socioeconomic status. Another methodological problem can occur if the study does not take into account whether the child is a boy or girl and whether the family is low or high in socioeconomic status. With respect to sex differences, boys engage in more disruptive behavior, school truancy, and verbal and physical violence than girls (Cullinan & Epstein, 1982; Hyde, 1984; Maccoby & Jacklin, 1980). This may be one of the reasons parents are more likely to spank boys more than girls, as was shown in Chapter 2 and by Simons et al. (1994). Thus, part of the relationship between spanking and a child's antisocial behavior may reflect the fact that boys misbehave more and parents are more likely to spank boys to correct the misbehavior. This is what is known as confounding of the relationship between spanking and antisocial behavior with the sex of the child (Hoghughi, 1992). There is also the possibility that spanking has different effects for boys and girls. This is what is known as an interaction effect or a moderator effect. We, therefore, examined whether the relation of spanking to antisocial behavior is different for boys and girls.

A similar problem applies to socioeconomic status and racial or ethnic group because, as was shown in Chapter 1, low socioeconomic status parents and parents from some minority groups spank more (see also Bank, Forgatch, Patterson, & Fetrow, 1993; Giles-Sims et al., 1995; Sears, Maccoby, & Levin, 1957; Straus, 2001a). Children from low socioeconomi.c status families, moreover, havl higher rates of antisocial behavior and delinquency (Bank et al., 1993; Feshback, 1970; Junger-Tas, Haen Marshall, & Ribeaud, 2003; Simons, Gordon',Simons, & Wallace, 2004). These two factors together can present a methodological problem. It is especially important to investigate whether the effect of spanking differs by racial or ethnic group because it has been argued that, in the context of a community where spanking is the cultural norm, spanking does not carry the same harmful side effects. This is believed to be the case because children who are raised with different norms concerning spanking do not equate spanking with parental harshness or rejection (Gunnoe & Mariner, 1997; Larzelere, Baumrind, & Polite, 1998; Polite, 1996) and therefore suffer no ill effects.

Effect of age of the child. Spanking might have different effects at different child ages. For example, it is widely believed that spanking toddlers, if done in moderation, does not have harmful side effects (Friedman & Schonberg, 1996a), whereas spanking older children and teenagers is thought to interfere with the transition to adulthood and autonomy. However, there does not seem to have been any empirical research on this issue. Thus, the advice to spank only young children is based on cultural tradition rather than scientific evidence. It is at least equally plausible to argue the opposite-that spanking toddlers will have a greater effect because it occurs at crucial developmental stages. Indeed, the results of the study described in Chapter 1 0 show that the effect of spanking on mental development is greater for younger than older children. Because there are plausible grounds for expecting age differences, we repeated the preliminary analysis for children of three age groups: 3 to 5 years, 6 to 9 years, and 10 years and oyer. The preliminary results were parallel for all three age groups. As a consequence, for the reasons given in the section of the Appendix for this chapter, the final analysis was conducted only for children aged 6 to 9.

Correlation of Spanking with Antisocial Behavior

The data permitted computing correlations between the frequency of spanking and the child's antisocial behavior. Fifteen of the correlations are on the relation of spanking to antisocial behavior in the same year ( contemporaneous correlations), and 15 examine the relationship of spanking at Time 1 to antisocial behavior two years later (time-lagged correlations). All 15 contemporaneous correlations, and all15 time-lagged correlations found that the more frequently a mother spanked her child in the week she was interviewed, the more antisocial behavior that year and also two years later. (The correlation coefficients are in Straus, Sugarman et al., 1997.

Following the recommendation of Bruning and Kintz (1987), we investigated whether the size of the correlations differed by year of measurement or by the age and sex of the child. We found that, with only two small exceptions, the relation between spanking and antisocial behavior was consistent across all ages and all years of interviews, and across gender (see Straus, 1997, Table 1 ). The fact that spanking was correlated with antisocial behavior to about the same extent for 3- to 5-year-old children as for older children is very important. It suggests that, contrary to both popular and professional beliefs (Friedman & Schonberg, 1996a), spanking is just as harmful for toddlers as it is for other age groups.

Spanking and Change in Antisocial Behavior

For the reasons explained previously, ordinary correlations may be misleading. What seems to be an effect of spanking on antisocial behavior could really be the effect of some underlying variable such as socioeconomic status or lack of parental warmth. The most important limitation of ordinary correlations is that they provide no information to distinguish cause from effect. Does spanking cause antisocial behavior or does antisocial behavior cause spanking? To deal with these problems, we used the statistical method known as analysis of covariance. This controlled for differences in family socioeconomic status, sex of the child, and the extent to which the home provided emotional support and cognitive stimulation. Most important, it controlled for the amount of antisocial behavior at the start of the study. The results of testing the hypothesis with this method can determine whether there is a change in children's antisocial behavior two years later (i.e., subsequent to the year in which the spanking occurred and whether that change is in the form of an increase or a decrease in antisocial behavior). It can also determine whether there is an effect of spanking that is over and above the effect of family socioeconomic status, sex of the child, and the extent to which the home provided emotional support and cognitive stimulation.

Chart 6.1 graphs the results of the analysis of covariance. At the left side of the chart are the children whose parents did not spank them during the week studied in the first year of the study. Those children had an average decrease of four points on the antisocial behavior scale. Moving from left to right in Chart 6.1 to the children who were spanked once during the Time 1 week, shows that their antisocial behavior score increased by an average of two points. The children who were spanked twice also had about a two-point increase in antisocial behavior. The biggest change in antisocial behavior was for children spanked three or more times that week. Their antisocial behavior score increased by an average of 14 points. Thus, the more frequent the spanking in 1988, the greater the increase in antisocial behavior over the subsequent two years. Only among children who were not spanked the week before the Time 1 interviews did antisocial behavior decrease. The F tests and other statistics for these results are in Table 2 of Straus, Sugarman et al., 1997.

Chart 6.1 Children Who Were Not Spanked Decreased Antisocial Behavior, whereas Children Who Were Spanked Increased Their Antisocial Behavior Two Years Later. (Chart not available)

*Mean adjusted for T1 antisocial behavior, T1 cognitive stimulation, T1 parental emotional support, child gender, race, and socioeconomic status.

It is important to keep in mind that the terms increase and decrease describe change compared with other children in the study at each point in time. In absolute terms, the average amount of antisocial behavior decreases as young children mature (Tremblay, 2003). The way we measured antisocial behavior takes this average improvement in children's behavior into account because it measures how far above or below the average antisocial behavior of all children in the sample each child is at each time point.

Does the Context Make a Difference?

the results also provide information on whether the presence or absence of the variables we controlled affected the relation of spanking to antisocial behavior. As explained previously, it is widely believed that, if parents are loving and supportive, spanking does not have a harmful effect. When we investigated that possibility, we did not find a statistically significant interaction or moderator effect for emotional support. That is, spanking was associated with an increase in antisocial behavior among children whose parents were high in emotional support as well as among children of low-support parents. The fact that, even when there is lots oflove and support, spanking is associated with an increase in antisocial behavior does not mean that love and support make no difference. Our study, like many others, found that the more supportive the parent, the lower the average level of antisocial behavior.

We did find that the relation of spanking to antisocial behavior was influenced by two other variables. Chart 6.2 shows that the tendency for spanking to be related to an increase in antisocial behavior two years later is stronger for boys than for girls, and Chart 6.3 shows that the relation between spanking and antisocial behavior is stronger for White children compared with minority children. Nevertheless, although the amount of increase in antisocial behavior associated with spanking may be smaller for girls and minority group children, both experienced an increase in antisocial behavior in proportion to the amount of spanking they had experienced two years earlier.

The result for minority group children is particularly important because many minority group parents believe that under the high crime conditions of inner city life, their children need (to use one of many euphemisms for spanking) "strong discipline" (Alvy & Marigna, 1987; Kohn, 1969; Peters, 1976; Polite, 1996; Young, 1970). Children growing up in those difficult circumstances no doubt need closer supervision and control, but these results suggest that attempting to do this by spanking increases rather than reduces the risk that children will get into trouble. Other studies that also found that the harmful effects of spanking apply in different cultural contexts are in Chapters 10 and 14. See also the review by Lansford (2010).

Summary and Conclusions

We found that the more spanking by the mothers in this sample, the greater the chances that two years later the child would have an increase in antisocial behavior. The tendency for spanking to be associated with an increase in antisocial behavior applies regardless of the extent to which parents provide cognitive stimulation and emotional support, and regardless of socioeconomic status, ethnic group, and sex of the child. These results are contrary to the idea that, if parents provide adequate warmth and cognitive stimulation, spanking will not harm children. Our results are also contrary to the idea that spanking works better among lower socioeconomic status families or in some minority families. Moreover, the findings are consistent across years (1986 to 1988, 1988 to 1990), across types of analysis (multiple regression and analysis of covariance), and for all three age groups (ages 3 to 5, 6 to 9, and 10 and over). The consistency across age groups is important because it contradicts the widespread belief, held by both the general public and professionals advising parents, that spanking is acceptable if confined to preschool-age children. As we noted in Chapter 2, the consensus statement from an American Academic of Pediatrics conference in 1996 permitted spanking for children age 2 to 6. If the results in this chapter, and those in Chapter 10 on spanking and cognitive ability, had been available at that time, the outcome of that conference might have been very different.

Chart 6.2 The Increase in Antisocial Behavior Associated with Spanking Is Much Greater for Boys than for Girls (Chart not available)

*Mean adjusted for T1 antisocial behavior, T1 cognitive stimulation, T1 parental emotional support, child gender, race, and socioeconomic status.

Another question that is often raised is, "Does only one spanking make a difference?" We found that the increase in antisocial behavior starts with children whose mothers spanked them only once during the week of the survey. This is consistent with the results of studies by Larzelere and Grogan-Kaylor. Larzeler (1986) found ''there is no evidence that a threshold frequency of spanking is necessary before it begins to influence child aggression" (p. 31). Grogan-Kaylor (2004) found that even relatively infrequent spanking is associated with an average increase in antisocial behavior compared with children whose parents did not spank to correct misbehavior.

Chart 6.3 Spanking Increases Antisocial Behavior by Both White and Minority Children, but the Effect Is Slightly Less for Minority Children (Chart not available)

*Mean adjusted for Tl antisocial behavior, Tl cognitive stimulation, Tl parental emotional support, child gender, race, and socioeconomic status.

Since the study in this chapter was done, there have been at least 14 other longitudinal studies that have found that spanking is associated with a subsequent increase in maladaptive behaviors. Chapter 19 reviews those that examined whether spanking is associated with an increase in the probability of antisocial behavior and crime. It is important to understand the implications of the phrase "an average increase." When there is an average effect, it means that there will be children for whom the effect of spanking is greater than the average effect and children for whom the effect is less than the average. Or putting it another way, spanking does not always lead to an increase in antisocial behavior. As explained in Chapter 1, the effect of risk factors such as spanking is always in the form of an increased probability of the harmful effect, not a one-to-one relationship. A wellestablished example of a risk-factor effect is heavy smoking. About one third of heavy smokers die of a smoking"related disease (Matteson et al., 1987). But this high mortality rate also means that two thirds of very frequent smokers can point out that they smoked more than a pack a day all their life and have not died from a smoking-related disease. Similarly, most adults who were spanked can say, "I was spanked a lot and I'm OK." Although those who say these things are factually correct, the intended implication that smoking or spanking are safe is not correct. The correct implication is that such individuals are one of the "lucky ones." Thus, although most children who are spanked will not be high in antisocial behavior, that does not mean that spanking is harmless-just as the fact that most heavy smokers do not die, it does not mean that smoking is harmless.

The chapters that follow, and much other research, show that the behavior problems associated with spanking are not confined to aggression and other antisocial behavior. In addition, these studies, like the present chapter, reveal a dose-response to spanking, starting with even one instance. The effect size for one instance is small, but it exists. The more frequent the spanking, the greater the probability of behavior problems. Taking the whole range of spanking as measured by this study, a rough estimate of the potential for reducing antisocial behavior can be obtained by comparing the change in antisocial behavior scores for children who were not spanked in the past week with scores of children who were spanked 3 or more times in the past week. The score on the antisocial behavior scale of the children who were spanked 3 or more times is 18-points higher than the none group. The 6- to 9-year-old children in the 3-or-more-times group, who are 1 0% of the children in the study, would have had the greatest chance of improved behavior if their parents had not spanked them. In addition, because Chart 6.1 shows that even one instance of spanking in the previous week is associated with an increased risk of antisocial behavior, an additional 19.8% of children could benefit by a reduction in spanking from once to never, and 14.1% could benefit by a reduction from twice to once in a week. This comes to a total of 44% of the children in this national sample whose antisocial behavior could have decreased if their parents did not spank them or spanked them less often.

7 Impulsive Spanking, Never Spanking, and Child Well-Being

Impulsive behavior consists of acts carried out with little or no forethought or control, hot-tempered actions, acting without planning or reflection, and failing to resist urges (Hoghughi, 1992; Lorr & Wunderlich, 1985; Monroe, 1970; Murray, 1938). Parents may spank impulsively, or they may follow the recommendations of some advocates of corporal punishment such as Baumrind, Larzelere, and Cowan (2002) who find spanking acceptable if done as well-regulated spanking, that is, in a calm and collected way. Others believe in striking while the iron is hot. John Rosemond, the author of best-selling books on child rearing says that he believes in "spanking as a first resort; spanking in anger" (Rosemond, 1994a).

Vera E. Mouradian is the coauthor of this chapter.

Violence is the use of physical force to cause pain or injury (Gelles & Straus, 1979). Corporal punishment of children (spanking) is a legal form of violence, provided it causes only pain and not lasting physical injury and is for purposes of correction and control. The child who is spanked impulsively experiences physical attacks as part of one of the most crucial social relationships in their lives. As these experiences become internalized, they provide a model for the child's own behavior. Thus, impulsive spanking may be an important risk factor for impulsiveness in the child. This process may be an important one for understanding the development of criminal behavior. The criminogenic nature of impulsiveness has been shown in a number of studies, including a longitudinal survey of 411 London boys that demonstrated that "low intelligence, an impulsive personality, and a lack of empathy for other people are among the leading individual characteristics of people at risk for becoming offenders" (Farrington & Welsh, 2006, page V). Studies by Aucoin, Frick, and Bodin (2006) and Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, and Wellman (2005) found that the more spanking experienced by children, the higher their scores on a measure of impulsiveness. But because neither study distinguished between parents who spanked impulsively and those who did not, this correlation might reflect the part of the sample whose parents spanked impulsively. We believe that regardless of whether it is carried out impulsively or in a planned way, spanking increases the probability of antisocial behavior by the child. We also believe that this effect is even greater when the spanking is impulsive because, in that situation, spanking models not only violence but also impulsiveness. The study described in this chapter addressed the following questions:

* What percent of children were never spanked?

* When parents spank, how often do they spank impulsively?

* Are mothers who spank often more likely to do so impulsively?

* Is spanking related to impulsivity and antisocial behavior in children, even when the spanking is not done impulsively?

* Is spanking more strongly related to impulsivity and antisocial behavior in children when the spanking is impulsive than when it is planned?

* Are children who were never spanked less impulsive than those who have ever been spanked?

* Does maternal warmth and nurturance moderate the relationship of spanking to child antisocial and impulsive behavior?

Impulsi;ve Spanking and Child Behavior Problems

It has been 60 years since Sears et al. (1957) found that spanking by parents was associated with a less well-developed conscience and higher levels of aggression in children. Some argue that the relationship between spanking and aggression by children depends on whether spanking is used impulsively or in a controlled way (Dobson, 1988; Friedman & Schonberg, 1996a; Larzelere, 1994), reflecting a belief that only impulsive spanking has harmful side effects. Others, however, recommend that parents spank in anger (e.g., Rosemond, 1994a, 1994b ), and many parents have told us that to do otherwise is coldblooded. This discussion raises two questions. One question is to what extent parents spank impulsively. The other question is whether spanking in general, or only impulsive spanking, is associated with child behavior problems. These questions are examined by reviewing previous research and then by presenting new research fmdings.

Prevalence of Impulsive Spanking

Only three studies were found that provided data on the prevalence of impulsive spanking, and even these two did not use the term impulsive to describe their findings. However, their definitions are consistent with what we are calling impulsive spanking: spanking little or no forethought or control, hottempered actions, without planning or reflection. Carson (1986) studied 186 parents in a small New England city. Her findings can be interpreted as showing that about one third of those parents spanked impulsively. Holden and Miller (1997) differentiated between instrumental spankers and emotional spankers. Emotional spankers felt irritated, frustrated, and out of control when spanking their children. They constituted just under one third of the sample of 90 parents who used spanking. In addition to these two studies of actual incidents of spanking, we located two other studies that provide an indication of the potential for parents to use spanking impulsively. A Canadian national survey (Institute for the Prevention of Child Abuse, 1989) found that 80% of parents said that, at least on rare occasions, they came close to losing control when disciplining their children. A study by Frude and Goss (1979) found that of 111 mothers, 40% were worried that they could lose control and possibly hurt their children. A third and longitudinal study of 132 parents from a southwestern urban region examined the context in which spanking occurs (Vittrup & Holden, 2010; Vittrup, Holden, & Buck, 2006). The authors found that almost a third (29%) of parents reported feeling angry while they were spanking, which could also be related to impulsivity.

Effects of Impulsive Spanking

A search of electronic databases did not locate studies of specific effects of impulsive spanking on children. However, two of the three studies just cited provide some indirect evidence of the relation of impulsive spanking to specific child behaviors. Holden and Miller (1997) found that emotional spankers were less likely to believe that spanking would result in achieving their goals for the child, such as immediate compliance, good behavior, and respect for authority. Similarly, Carson (1986) found parents who spanked when they lost control tended to be more likely to see spanking as ineffective. Therefore, parents seem to believe that the impulsive administration of spanking undermines its effectiveness. In addition, impulsivity implies lack of consistency in punishment, and inconsistent punishment has been found to be associated with lower levels of parenting self-efficacy (Acker & O'Leary, 1988).

There are theoretical grounds for expecting adverse effects of impulsive spanking on children. First, we could expect that impulsivity in the parent would provide a model of impulsivity for the child. Impulsivity in children has been found to be associated with conduct disorders and antisocial behavior, among other problem behaviors (Hoghughi, 1992; Olson et al., 2005; Schweinle, Ickes, Rollings, & Jacquot, 2010). Moreover, impulsivity in the form of low self-control is the core explanatory variable of the general theory of crime (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Rebellon, Straus, & Medeiros, 2008).

A child who experiences impulsive spanking may come to believe that the punishment results from the characteristics of the parent, rather than for the child's good. When spanking is perceived as parent-centered, it may be more likely to create resentment and anger, undermining the parent-child bond that is critical to preventing antisocial behavior (see Chapters 8 and 9). Impulsive spanking may also be more stressful for children, because it is less predictable and associated with more negative parental emotion. In other words, erratic spankings by an angry parent are probably more stressful for the child than spankings that follow some kind of consistent guidelines (e.g., every time a child throws a ball inside the house after repeated commands to stop).

Effects of Never Spanking

At the other end ofthe spanking continuum from impulsive spankers are parents who never spank. These parents are important to furthering our understanding of the effects of spanking on children. It is widely believed that spanking is sometimes necessary and that without it, children's behavior will become , out of control and increasingly antisocial. Although the results of the study presented in the previous chapter demonstrate that spanking increases the probability of antisocial child behavior, they do not refute the prediction of those who believe that never spanking would be harmful because that sample did not include a group who never spanked. The no-spanking group in that study were mothers who did not spank in the previous week. But there are 51 other weeks in the year, to say nothing of previous years. The data presented in this chapter permitted us to study the children of mothers who never spanked, as well as those who spanked impulsively

The concerns that parents who never spank will lack effective control and that their children will have behavior problems were put forward at a community meeting iJt one of the cities where the present study was conducted. The meeting was held to discuss a proposed community initiative to end or reduce spanking. One of the parents attending said, "If you nuts have your way, we're going to be a town with kids running wild!" At the same meeting, those wanting a communitywide effort to reduce or end spanking made exactly the opposite prediction. They argued that, on average, children who are never spanked will have lower rates of delinquency and fewer psychological problems in childhood and as young adults.

The importance of this controversy cannot be overestimated. Some of the most sophisticated defenders of spanking, such as Baumrind and Larzelere (e.g., Baumrind et al., 2002) deny that they approve of spanking. But they say that spanking is a safe and necessary backup. As a consequence, the most crucial test, for both opponents and advocates of spanking, focuses on the children of parents who never spank. However, there does not seem to have been a study conducted that compared never-spanked children with those spanked very rarely. This is a crucial missing link in the research on spanking because spanking only as a backup is the advice, not just of Baumrind and Larzelere, but of almost all the pediatricians and parent educators with whom we have discussed this issue. Although most are now against spanking, they are unwilling to say that children should never be spanked.

The data for this study enabled us to identify children in the sample who were never spanked. As a consequence, we can make a start on resolving this critically important issue. Four hypotheses were tested:

1. The more spanking used by the mother, the greater the child's impulsiveness and antisocial behavior.

2. The more impulsive the spanking, the greater the child's impulsiveness and antisocial behavior.

3. Spanking is associated with antisocial behavior and impulsiveness by the child only when spanking is impulsive.

4. Children who were never spanked have the lowest levels of antisocial behavior.

Sample and Measures

These hypotheses were tested using data on a representative community sample of mothers ofl,003 children, aged 2 to 14, living in two counties in Minnesota. The data were obtained in 1993 by telephone interviews with the mothers. The children were primarily from two-parent families (95.1 %). They were about equally divided between boys (54%) and girls (46%), and their mean age was 8.6 (median 9). The mean and the median age of the mothers was 37. They had been married an average of 13.9 years and had a median of two children living at home (mean= 2.5). Consistent with census data on the socioeconomic composition of these two communities, the sample was almost entirely Caucasian, and 31% of the mothers and 35% of the fathers were college graduates. Additional information on the sample is in Straus & Mouradian (1998).

Measures

Spanking. The mothers were asked how often in the past six months they had spanked, slapped, or hit the child when the child "does something bad or something you don't like, or is disobedient." The response categories, which are taken from those used in the Conflict Tactics Scales (Straus et al., 1998; Straus & Mattingly, 2007), were never, once, twice, 3 to 5 times, 6 to 10 times, 11 to 20 times, and more than 20 times.

Children who were never spanked were identified on the basis of two questions that asked the mother the age at which spanking was first used and the age at which spanking was used the most. If the mother responded to both of these questions that she never spanked her child, we classified the child as not having been spanked. We used these data to classify the children into the following categories: never (189 children); not in the past six months (408 children); once in the past six months (98); twice in the last six months (81 children); 3 to 5 times (86 children); and 6 or more times (71 children). Thus, even in this low spanking community, only 20% of the children had never been spanked.

Other discipline. We measured non-corporal punishment discipline by asking the mothers how often in the past six months, when the child had done something bad, had done something the mother did not like, or had been disobedient, that she "Talked to him or her calmly about a discipline problem, sent him or her to his or her room, or made him or her do 'time-out,' took away something, or took away some privilege like going somewhere." Response categories were never, once, twice, 3 to 5 times, 6 to 10 times, 11 to 20 times, and more than 20 times. Response categories were transformed to the midpoints of the category (3-5 = 4, 6-10 = 8, 11-20 = 15, more than 20 = 25) and were summed. The resulting non-corporal punishment intervention scale scores ranged from 0 to 7 5 with a mean of26.6 and a standard deviation of19 .6. The alpha reliability was .71. The scores were grouped into the following four categories for use in the ANOVAs: 15 times or less frequently (n = 326), 16--30 times (n = 244), 31-45 times (n = 196), and more than 45 times (n = 167).

Antisocial behavior by the child. Antisocial behavior was measured by asking the mother about 11 behaviors that involved acting out against other people including the child's family, teachers, and peers. Eight of the items were asked regardless ofthe age of the child: How often in the past six months the child was cruel or meanto other kids, a bully; cruel, mean to, or insulting to the mother; in denial of doing something he or she really did; hitting a brother or sister; hitting other kids; hitting you or other adults; damaging or destructive to things; and stealing money or something else. The remaining three items depended on the age of the child. Mothers of preschool-age children (2 to 4) were asked how frequently their child "refuses to cooperate; repeats misbehavior after being told not to do it; and misbehaves with a baby sitter or in day care." Mothers of school-age children were asked how frequently their child "disobeys you; is rebellious; and has discipline problems at school." The response categories for all items were: 0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, and 3 = frequently. The alpha reliability for this scale was .81.

Child impulsiveness. This was measured by two items asking how frequently in the previous six months the child had "temper tantrums, hot temper" and "acts in unpredictable, explosive ways, impulsive." These items were chosen to reflect two often-cited features of impulsivity: acting quickly without apparent thought or a lack of planning, or failing.to resist urges (Hoghughi, 1992; Lorr & Wunderlich, 1985; Murray, 1938) and being quick or hot-tempered (Hoghughi, 1992; Monroe, 1970). Response categories for these items were: 0 =never, 1 = rarely, 2 =sometimes, and 3 =frequently. The item scores were transformed to Z scores and summed. The alpha reliabilitY score for this scale was .56. Scale scores were normalized and transformed into ZP scores. The correlation between the child antisocial behavior scale and the child impulsiveness scale measure was .60. Although this is a substantial correlation, 64% of the variance is not shared, leaving open the possibility that the findings on child impulsiveness could differ from those for antisocial behavior. In fact, we expect that impulsive corporal punishment will be more strongly related to child impulsiveness than to antisocial behavior because that relationship could reflect modeling, which is a more direct linking process than the processes which might bring about a relationship with antisocial behavior, such as anger and resentment.

Control variables. The analyses controlled for five characteristics of the families and the children that might influence the relationship between spanking and child behavior problems: the mother's nurturance, the age of the child, the child's sex, the family's socioeconomic status, and the child's level of problem behavior. The interaction or moderating effect of these five variables was also tested using analysis of covariance. The tests for interaction provide data on whether the effect of spanking is different when one of these five variables is present or absent, or low versus high. An example of a test for an interaction effect is the analysis of the widely held belief that spanking is not harmful when it is done by loving parents. We tested that theory in the previous chapter and in the chapter on the link between spanking and risky sex in adulthood (Chapter 9) and found that the harmful side effects of spanking were present even for children with warm and supportive mothers. The implications for the relation of spanking to crime and violence in society are discussed in Chapter 19.

The Question of Causality

In the previous chapter, we pointed out that if a study finds a correlation between spanking and child behavior, this could mean that the spanking is affecting the child's behavior or that the child's behavior is eliciting spanking. We believe that both are true. That is, misbehavior can lead parents to spank, but if parents do spank, the longitudinal studies, such as the studies on child antisocial behavior (Chapter 6), mental ability (Chapter 10), adult crime (Chapter 15), and several other studies summarized in Chapter 19, have found that spanking tended to make children's behavior worse. We can draw that conclusion because the longitudinal studies included information on the child's behavior at the time of the spanking and then two years later, making it possible to determine whether the problem behavior decreased or increased among children who were spanked. All of the longitudinal studies conducted to date have found that, on average, spanking makes children's behavior worse.

The study described in this chapter did not have follow-up data on the children. However, we were able to take other steps to control for the level of misbehavior that led the parents to spank. We developed a scale to measure the extent to which the mother used discipline methods other than spanking, such as deprivation of privileges, explaining, and time-out. Use of this scale is based on the assumption that parents would not engage in these disciplinary interventions if there were no misbehavior (as perceived by the parent). Therefore, it is plausible to assume that the frequency of these disciplinary interventions reflects the extent of the child's misbehavior. To the extent that this is correct, the nonviolent interventions scale controlled for the misbehavior that led to the corporal punishment.

Prevalence of Spanking and Impulsive Spanking

Prevalence of Spanking

Consistent with all other studies, such as the one on the use of corporal punishment in the United States (Chapter 2), we found that the younger the child, the larger the proportion of mothers who hit their child during the previous six months:

59.3% of mothers of children aged 2 to 4

45.8% of mothers of children aged 5 to 9

20.5% of mothers of children aged 10 to 12

14.4% ofmothers of children aged 13 to 14

These are high rates, but they are much lower than those found for other representative samples of American children (see Chapter 2 and Giles-Sims et al., 1995; Straus, 2001a). Part of the reason for the lower rate of spanking may be because this study asked about spanking in the previous six months, as compared with the previous year for the other studies. It may also reflect the fact that the study was done in the state of Minnesota, which is a state that has long had a social and cultural climate that is favorable for children. Ever since the Annie E. Casey Foundation started annual publications that compared states on 10 indicators of child well-being, Minnesota has been in the top group. In the 2006 ranking, Minnesota ranked fourth in the nation (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2006). Minnesota is also a state with a high average level of education, and it is the only state in the United States that has required every county to collect a tax to pay for parenting education. Perhaps most directly related to the relatively low rate of spanking for the mothers in this study is that one halflived in a city that had a Positive Parenting community-wide program to end the use of spanking sponsored by the Minnesota Cooperative Extension Service.

Relation of Spanking and Impulsive Spanking to Child's Antisocial Behavior

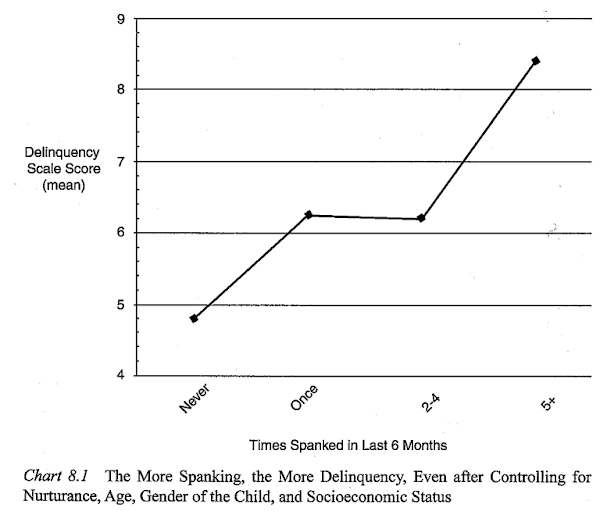

Chart 7.1 shows that the more spanking by the mother, the greater the antisocial behavior by the child. This is the same result as was shown in the previous chapter for children in a national sample. However, this study goes beyond the previous chapter in two important ways. The first advance is that it provides data on impulsive spanking. Chart 7.2 shows that impulsive spanking is even more strongly related to antisocial behavior than is spanking in general. The analyses of covariance used to obtain the results in these two charts are in Straus (1998, Tables 1 and 2).

The second advance over the study in the previous chapter is that it identified children who were never spanked. This enabled an important issue to be investigated for the first time in any study of spanking. This is whether there is a difference between children whose parents spanked only very rarely and those who did not spank at all. Both Chart 7.1 and 7.2 show that the neverspanked group at the left side of the chart had much less antisocial behavior than any other group, including the second group: children whose mothers did not spank at all in the past six months but had spanked previously. Three of the other five variables we examined were also significantly related to antisocial behavior: (1) the more nurturing the mother, the lower the child's antisocial behavior, (2) girls had lower antisocial behavior scores than boys, and (3) the more nonviolent discipline, the higher the antisocial behavior. This is probably because nonviolent discipline like spanking tends to occur in response to the amount of antisocial behavior.

Chart 7.1 The More Spanking, the More Antisocial Behavior

Context Effects

The analysis for this study was done in a way that investigated whether the effect of spanking depends on whether the spanking was impulsive. The results showed that:

* The relation of spanking to antisocial behavior was greatest for the children whose mothers were most impulsive in using spanking-those who spanked impulsively one half or more of the time (upper line of Chart 7.3).

* The children in the never-spanked group had the lowest antisocial behavior. Thus, any amount of spanking, even when it occurred prior to the past six months, was associated with greater antisocial behavior than that by children of mothers who never used spanking.

* Among mothers who reported only rare impulsive spanking (dotted line in center of Chart 7.3), all five comparisons with children who never experienced spanking showed that the never-spanked children had lower antisocial behavior scores. This means that when there was any impulsive spanking in the past, even though there was none in the past six months, or when there was even occasional impulsive spanking, it is associated with more antisocial behavior than by children of mothers who never spanked.

* The solid line at the bottom of Chart 7.3 is for children of mothers who reported no impulsive spanking. This line shows that, even when there was no impulsive spanking, spanking is associated with more antisocial behavior. The bottom line in Chart 7.3 shows a decrease in antisocial behavior for the two highest levels of spanking. However, because mothers who never spank impulsively also are infrequent spankers, there are very few children in those two categories. As a consequence, the seeming decrease is not statistically dependable-see footnote to Table 1 in Straus (1998), and we do not think any importance should be attached to that seeming decrease with more spanking.

Chart 7. 2 The More Impulsive Spanking, the More Antisocial Behavior

We also investigated whether the effect of spanking and impulsive spanking depends on one or more of the five other variables listed in the Hypotheses section. The only one of these five that made a difference was the amount of nurturance provided by the mother. With the exception of one data point, within each level of nurturance, the more spanking and the more impulsive the spanking, the higher the average antisocial behavior. Thus, although children of nurturing mothers had lower antisocial behavior scores, spanking still had an important adverse effect.

Chart 7.3 Spanking Is Most Strongly Related to Child Antisocial Behavior When Spanking Is Impulsive

*Means adjusted for mother's impulsive spanking, mother's nurturance, mother's non-spanking interventions, child's age, child's sex, and family socioeconomic status.

Child's Impulsive Behavior

The three previous charts are about antisocial behavior by the child. In this section, the focus is on impulsive behavior by the child. Chart 7.4 shows that the more spanking, the more impulsive the behavior of the child. Chart 7.5 shows that the more impulsive the spanking, the more impulsive the child. For impulsive spanking, there is an almost one-to-one increase in child impulsiveness as the mother's impulsive spanking increases, and the differences are large. The dashed line at the top of Chart 7.6 shows that the relation of spanking to impulsive behavior by the child is greatest when mothers use spanking impulsively half or more of the time. For children of these mothers, even one instance of spanking in the prior six months was strongly associated with children being much more impulsive than among children who did not experience spanking during the six month referent period or who were never spanked. Among mothers who only rarely were impulsive when spanking, the dotted line in the center of Chart 7.6 shows that as spanking increases, there is a step-by-step increase in child's antisocial behavior. For the most part, any spanking, past or present, was associated with more child impulsiveness than for children in the never-spanked group.

Chart 7.4 The More Spanking, the More Impulsive the Child

The relation of spanking to impulsiveness of children was weakest, but still present for children of mothers who spanked nonimpulsively (solid line at the bottom of Chart 7 .6). As the frequency of spanking increased, impulsiveness increased, but only up to the "twice in the last six months category" of spanking, and then decreased. These decreases were not statistically dependable because there were very few cases in those two groups of children and are best regarded as chance occurrences.

Do the other five variables affect the relation of spanking to impulsive behavior by the child? The statistical tests found that the sex of the child and the socioeconomic status of the family made a difference in the relation of spanking to children's impulsiveness. There was a stronger relation between spanking and impulsive behavior by boys than by girls. Although the statistical analysis showed a significant interaction of family socioeconomic status with spanking, we were unable to identify a meaningful difference between low and high socioeconomic status families in the relation of spanking to impulsive behavior by children.

Chart 7.5 The More Impulsive Spanking, the More Impulsive the Child

Summary and Conclusions

This study found that the more spanking is used, and the more impulsive it is, the more likely children are to be impulsive and antisocial, even after controlling for five other variables that could influence the effects of spanking. These results cast serious doubt on the recommendation of a conference of pediatric and other child behavior specialists that endorsed the use of spanking with children age 2 to 6, if done by loving parents (Friedman & Schonberg, 1996a). If this view were correct, we should have found that spanking was related to child misbehavior only among older children, and only among children with mothers who were less nurturing. Instead, the results of this study show that the tendency for spanking to be associated with more antisocial behavior and impulsiveness by the child applies to all age groups, regardless of the level of maternal nurturance---see Straus and Mouradian (1998) for tables giving the detailed results of the analyses of covariance.

Although the relationship between spanking and child behavior problems is weaker for children of mothers who were not impulsive spankers, it was strong enough for there to be a statistically dependable relationship between spanking and child behavior problems, even when spanking is not done impulsively.

Chart 7. 6 Spanking Is Most Strongly Related to Child Impulsiveness When Spanking Is Impulsive

*Means adjusted for mother's impulsive spanking, mother's non-spanking interventions, child's age, child's sex, and family socioeconomic status.

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

One type of limitation is the fact that this study measured only two aspects of spanking: frequency and impulsiveness, and there are a number of other aspects needed for a complete understanding of spanking. For example, since conducting the study in this chapter, we developed the Dimensions of Discipline Inventory (Straus & Fauchier, 2011), which includes measures such as the degree to which explanation and support accompany spanking, as well as measures of eight other methods of correcting misbehavior.

The most important limitation of this study is that the findings are based on cross-sectional, rather than longitudinal or experimental, data. We attempted to take into account the fact that spanking is typically a response to child misbehavior by using a scale to measure nonviolent discipline as a proxy for child misbehavior. The results showed that spanking, and especially impulsive spanking, was associated with more child antisocial behavior and impulsiveness regardless of the level of misbehavior that led to the spanking. We interpret this as evidence that when spanking is used in addition to other disciplinary strategies, it tends to make things worse. This interpretation is strengthened by the findings from the longitudinal studies on child behavior (Chapter 6), cognitive ability (Chapter 10), crime in adulthood (Chapter 15), and other longitudinal studies summarized in Chapter 19 and Straus (2001c). These studies found that the more parents respond to misbehavior at Time 1 by spanking, the greater the increase in undesirable behavior from Time 1 to Time 2.

This study also has two unique strengths. The first is that, rather than treating spanking as present or absent, or differentiating only on the basis of the chronicity of spanking, the study took into account another of the many other dimensions of spanking-whether it was done impulsively.

A second unique feature of this study is that it identified children who, at least according to the mother, had never experienced spanking. It is particularly important to learn about children who have not been spanked because it is so widely believed that spanking is sometimes necessary (see Chapter 18) and that if parents are not prepared to spank as a backup when other methods have not worked, the child will grow up being out of control. Thus, the inclusion of a never-spanked group in this study begins to fill a void in the literature. It can be considered a starting point for addressing individual and societal concerns about the effects of ending all spanking. With these strengths and weaknesses in mind, what can be concluded from this study?

The findings suggest that spanking and impulsive spanking increase the risk of children developing a pattern of impulsive and antisocial behavior. Moreover, we believe that spanking, especially impulsive spanking, are part of the etiology of the high level of violence and crime in society because about one half of parents used spanking impulsively at least some ofthe time and because the long-term risks associated with corporal punishment have been demonstrated by the longitudinal studies in this book and the many other longitudinal studies listed in Chapter 19.

At present, parents of toddlers who do not spank make up a small but growing portion of the population (see Chapters 2 and 17). What will happen when, as seems likely, no-spanking becomes more widespread? That is likely to happen because of the changes in society described in the concluding chapter. By 2011, 30 nations have chosen to follow the Swedish example and the recommendations of the European Union and United Nations by enacting laws against spanking by parents. Will it produce a generation of antisocial and out of control children as believed by those who think that spanking is sometimes necessary? The results in this chapter and the experience in Sweden described in Chapters 19 and 20 suggest that the opposite is more likely. The decrease in youth crime and drug abuse in Sweden since passage of the no-spanking law is consistent with that implication.

8 The Child-to-Mother Bond and Delinquency

There are a number of ironic aspects of spanking. One of the most frequent occurs when a parent spanks a child for hitting another child-which they are more likely to do than for most other misbehaviors. A national survey of 1,012 parents asked what punishment these parents would consider appropriate for three types of misbehavior. For ignoring a request to clean up their room 9% thought spanking was appropriate, for stealing it was 27%, and for deliberately hurting another child 41% approved of spanking (Kane-Parsons and Associates, 1987; see also Sears et al., 1957). The irony is that when parents hit a child to correct the child's hitting, they are inadvertently modeling the very behavior they want the child to avoid. This is one of reasons for the almost complete consistency between studies like those in Part IV and by many longitudinal studies documented in Chapter 19, which have found that the more spanking used by parents, the greater the physical aggression by the child.

Kimberly A. Hill is the coauthor of this chapter.

Studies that have found that spanking is associated with an increased probability of property crime as a child or adult (Grogan-Kaylor, 2004) are less easily understood than is the link between spanking and aggression. Except for the relatively rare parents who themselves engage in criminal acts, modeling is probably not an important part of the process linking spanking and delinquency. If it is not modeling, what social and psychological processes could account for the link between spanking and delinquency? The study in this chapter was designed to provide data on one of several possible processes. This is the possibility that, when parents spank, it tends to undermine the bond between child and parent, and the weakened bond in turn makes the child less receptive to parental guidance and more vulnerable to peer pressure and other factors that increase the probability of delinquent acts. In this chapter, we address the following questions:

* When spanking is used, does it weaken the bond between a child and his or her parents?

* If the parents who spank show warmth and support, does this avoid weakening the child-to-parent bond?

* Do children whose parents correct misbehavior by spanking engage in less or more delinquent behaviors?

* If spanking is done by warm and loving parents, does it override the tendency for spanking to be related to an increased probability of delinquency?

Does Spanking "Teach Him a Lesson"?

The caning of an American teenager in Singapore in the 1990s (Elliott, 1994) received national headlines and public discussion. It brought to the surface the widespread belief in the United States that spanking reduces delinquency. Many letters to the editor and comments on talk shows argued that if parents would go back to the good old-fashioned paddle, there would be less delinquency. The research evidence, however, suggests that the opposite is more likely. For example, in this book:

* Chapter 6 showed that the more spanking used by parents, the greater the probability that the child's antisocial behavior would become worse. However, tliis study was for young children and for antisocial behavior rather than statutory delinquency. * The 'five studies in Part IV all found that spanking was associated with an increased probability of crime later in life as an adult.

A few of the other studies include:

* A longitudinal study by Grogan-Kaylor (2005), which found that, after controlling for six other variables such as family income and cognitive stimulation by the mother, spanking was associated with an increase in antisocial behavior by the child, and that this applied across racial and ethnic groups.

* Welsh (1978) found that almost all the delinquent children in his sample had experienced a great deal of spanking by their parents.

* A study that followed up a large sample of boys from a high-risk area for 35 years found that spanking was associated with an increased probability of conviction of a serious crime as an adult (McCord, 1997).

* Straus (200 la, p. 1 08) found that, even after controlling for a number of other family characteristics, including socioeconomic status and whether there was violence between the parents, the more spanking the parent reported using, the greater the probability of the child being delinquent.

* Gove and Crutchfield (1982) found a number of parenting variables to be related to delinquency, including spanking, and that after controlling for all other variables, spanking remained significantly related to delinquent behavior.

* Conger (1976) and Rankin and Wells (1990) found that high parental punishment is associated with higher levels of juvenile delinquency. However, their measures of parental punitiveness included non-corporal punishment and yelling at the child. As a consequence, they do not provide direct evidence that spanking per se is related to delinquency.

* Simons, Lin, and Gordon (1998) found that adolescent boys who had experienced spanking were more likely to hit a dating partner, even after controlling for a number of factors such as parental involvement and support.

These are just a few of the 88 studies reviewed by Gershoff (2002). Fortynine of the studies tested the hypothesis that corporal punishment is associated with an increased probability of physical violence and antisocial or criminal behavior as a child and as an adult; of these, 97% found that corporal punishment was associated with an increased probability of physical violence, antisocial behavior, and crime. This degree of consistency of results is extremely rare in any field of science, and perhaps even rarer in child development.

Nevertheless, many of these studies have important limitations. In additi~n, there are a few well-designed studies that found no relationship between spanking and delinquency (e.g., Agnew, 1993; Simons et al., 1994). Therefore, one purpose of this chapter was to reexamine this issue by testing the hypothesis that spanking is associated with delinquency. The main purpose, however, was to test the theory that one of the reasons spanking increases the probability of delinquency is because spanking undermines the bond between children and parents.

The Child-to-Parent Bond and Delinquency

Spanking and other forms of corporal punishment may stop a specific undesired behavior at the moment, but in the long run, it may teach children to avoid particular behaviors only when they are in the presence of a parent or other authority figure who can impose a penalty, or some other circumstance where the probability of punishment is high. Obviously, that leaves a great deal of opportunity to engage in delinquent and criminal acts. As children grow older, they become less subject to parental observation and, in adolescence, they are usually too big to control by physical force. When this happens, avoiding delinquent behavior is largely dependent on the child having internalized behavioral standards (i.e., on the development of conscience).

Two aspects of spanking are likely to interfere with development of such internalized standards. First, as just noted, spanking places the focus on behaving correctly as a means to avoid punishment, rather than on behaving correctly in order to follow principles such as honesty, courtesy, compassion, prudence, and responsibility-the cognitions and emotions that together make up conscience. When parents spank to teach these principles, children do learn them, but we believe it is despite the spanking, not because of it. There is also a greater risk that some or all of what the parent wants to teach will be inadequately learned because fear and anger interfere with learning (see Chapter 10). The same moral instruction without spanking is likely to be more effective in facilitating a well-developed conscience.

A second aspect of spanking that interferes with the development of conscience is the tendency of spanking to weaken the bond between child and parent (Azrin & Holz, 1966; Barnett, Kidwell, & Leung, 1998; Bugental, Johnston, New, & Silvester, 1998; Mulvaney & Mebert, 2010; Parke, 1969). A strong child-to-parent bond is important because when there is a bond of affection with the parent, children are more likely to accept parental rules, restrictions, and moral standards as their own. These ideas are central to the social control theory of delinquency (Akers & Sellers, 2008; Hirschi, 1969). This theory links delinquent behavior to a weak social bond with parents and with other key institutions of society, such as the church, schools, and the workplace. The central idea of the social control theory is that law-abiding behavior depends, to a considerable extent, on the bond between a child and persons and organizations that represent the moral standards of society. A bond with parents refers to ties of affection and respect that children have for a parent. Hirschi argued that the bond or attachment to parents is the most important variable insulating a child against deviant behavior. It enables the child to internalize the rules for behavior and develop a conscience. The stronger the bond with the parents, the more likely children are to rely on internalized standards learned from parents when tempted to engage in a delinquent behavior (Hirschi, 1969, p. 86).

Hirschi's research and many empirical studies since then have found a link between a weak parent-child bond and juvenile delinquency. To take just four of these studies, Hindelang (1973) replicated Hirschi's study using rural adolescents 'and found that a weak bond to parents is also significantly related to juvenile delinquency in that environment. Wiatrowski and Anderson (1987) found that the weaker the bond with parents, the higher the probability of delinquency. Rankin and Kern (1994) found that a bond to both parents provides more insulation from delinquency than does a bond with one parent. Eamon and Mulder (2005) studied 420 Hispanic children and found that each increase of one point on the 15-point scale of parent-child attachment was associated with a 9% decrease in the probability of the child being in the high antisocial behavior category.

The relationship between the child-to-parent bond and delinquency is likely to be moderated by other variables, that is, to be contingent on other variables. Seydlitz ( 1990) found that the relation of some aspects of the bond with parents to juvenile delinquency depends on the age and gender of the adolescent. Several studies have also found an indirect relationship between bonds with parents and delinquency. For example, Agnew (1993) found that a weak bond with parents is associated with an increase in anger or frustration and an increased likelihood of association with delinquent peers, which in tum increases the likelihood of juvenile delinquency. Warr (1993) found that part of the reason for the link between bonding and delinquency occurs because a close child-toparent bond inhibits forming delinquent friendships. Marcos and Bahr (1988) found both a direct link between bonding and drug abuse and an indirect link through the relation of bonding to greater educational attainment, conventional values, inner containment (the ability to withstand pressure from peers), and religious attachment.

Although there is a large body of evidence showing a link between weak child-to-parent bonds and delinquency, there does not seem to have been a study investigating whether spanking weakens the child-to-parent bond. In fact, Hirschi himself doubts that it does (Hirschi & Gottfredson, 2005). This study was designed to help fill that gap in the chain,Of evidence linking spanking and delinquency.

Spanking and the Child-to-Parent Bond

If spanking is typically carried out in the hope of raising a well-behaved and lawabiding child, what could explain why so many studies have found that spanking is instead associated with delinquency? Given the many studies just reviewed showing that a weak child-to-parent bond is associated with delinquency, it is plausible to suggest that one of the reasons for the relationship between spanking and delinquency is that spanking undermines the bond between parent and child.

If spanking and physical abuse are conceptualized as low and high points on a continuum of violence against children, a link between spanking and attachment to parents can be inferred from a number of studies that show that physical abuse has an adverse effect on child-to-parent attachment.

* Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Zoll, and Stahl (1987) compared 10 maltreated infants, 18 non-maltreated high-risk infants, and 28 matched low-income controls on the Ainsworth Strange Situation test and found less adequate infant attachment among the maltreated children. (The Strange Situation experiment examines the attachment between very young children and parents.)

* Crittenden (1985) studied 73 mother-infant dyads referred by the welfare department and found that infants who were abused showed an avoidant or ambivalent pattern of attachment, and adequately treated infants showed a secure pattern of attachment.