12 What Explains the Link Between Spanking and Assaulting a Partner?

A substantial body of research, including the chapters in Parts II and III, has found that spanking or corporal punishment experienced as a child is associated with a broad range of serious behavior problems of children and adolescents. The chapters in this part of the book extend the inquiry to crime as an adult. This chapter and the next chapter are about the links between spanking and physically assaulting a romantic partner or spouse. Chapters 14 and 15 are about the relation of spanking to a broad range of criminal acts. Chapter 16 is about the relation of spanking to forcing sex on a partner. In the concluding part of the book, Chapter 19 summarizes the results of many studies of the relation of spanking to crime, with an emphasis on cross-cultural and longitudinal research. The questions to be addressed in this chapter include:

* What has previous research found about the link between being spanked as a child and later in life assaulting a marital or dating partner?

* What is the relationship of spanking to depression as an adult, to approving of violence, and to marital conflict?

* Are depression, approving violence, and marital conflict processes or mechanisms that explain why spanking is associated with an increased probability of assaulting a partner?

* Does the relation of spanking to assaulting a partner apply when the study controls for things that could be the underlying causes?

* Does the relationship between having been spanked as a child and assaulting a partner apply to assaults by women as well as men?

* Do the results apply to both minor assaults such as slapping a partner and severe assaults such as punching or choking a partner?

* What are the policy and practice implications of the results of the study reported in this chapter?

Spanking and Assaults on Partners

Studies over the last 35 years have found that spanking is related to physically assaulting a partner. Gelles (1974) studied 80 families and found that adults who had been spanked frequently as a child (at least monthly) had a higher rate of assaulting a partner than those who had not been hit. Carroll (1977) studied 96 couples and found that "36.6% of those who had experienced a high degree of parental punishment reported assaulting a spouse compared to 14.5% of those who had not." Other studies found similar results. Johnston (1984) studied 61 abusive men and 44 nonabusive men and found that spanking was related to both minor and severe spous~ abuse. Kalmuss's (1984) analysis of a nationally representative sample of 2,143 American couples found that being slapped or spanked as a teenager more than doubled the probability of husband-to-wife and wife-to-husband assaults.

Straus and Kaufman Kantor (1994) studied a second nationally representative sample and found that spanking was a significant risk factor for assaults on wives, even when other potentially influential variables, such as socioeconomic status, gender, age, witnessing violence between parents, and alcohol use, were controlled. Finally, a longitudinal study of high school boys (Simons et al., 1998) found that the more spanking these boys had experienced, the more likely they were to hit a dating partner. The Simons et al. (1998) study is important because it controlled for the level of misbehavior that presumably led' to the parents spanking when the boys were younger. This is critical because, as noted in previous chapters, parents tend to spank in response to misbehavior. Therefore, if a study does not control for the level of misbehavior in adolescents, it may reflect preexisting aggressive and antisocial tendencies of the boys who were spanked, rather than the effect of spanking.

The research showing that spanking is associated with an increased probability of physical assaults against a partner is consistent with many studies that have found that spanking is related to physical aggression against other children and to other behavior problems. This includes the studies on spanking and child behavior problems in Part II, the other chapters on the relation of spanking to adult violence and crime in this part of the book, and the studies reviewed by (Gershoff, 2002).

The Linking Processes

Previous studies have found that spanking is associated with physically assaulting a partner. But those studies do not show why spanking is associated with an increased probability of physically assaulting a partner. This chapter presents the results of investigating three of the many possible processes that could explain what produces the link between spanking and violence against a partner. The three mediating processes are:

* Corporal punishment teaches that it is morally correct to hit to correct misbehavior and that carries over to relationships between adults.

* Corporal punishment limits development of nonviolent conflict-resolution skills that results in a high level of conflict with partners and, therefore, a higher probability of violence.

* Corporal punishment increases the probability of depression, which in turn increases the probability of aggression.

The Morality of Violence

Although physically assaulting a partner is a criminal, act, American culture actually tolerates and legitimizes such acts in various ways. National surveys show that at least one quarter of the population approves slapping a spouse under some circumstances (Gelles & Straus, 1988; Greenblat, 1983; Moore & Straus, 1995; Simonet al., 2001; Straus et al., 2006; Straus, Kaufinan Kantor, & Moore, 1997). When asked for an example of such a circumstance, by far the most frequently mentioned circumstance was sexual infidelity (Greenblat, 1983, pp. 243-246). Among the university students studied for Chapter 13 on spanking and partner violence in 32 nations, the rates for approving of a husband slapping his wife under some circumstances ranged from 26% to 45%, and the rates for approving of a wife slapping her husband ranged from 65% to 82%.

These attitudes are partly a carryover from a previous historical era when husbands did have the legal right to physically chastise an errant wife (Calvert, 197 4 ). American courts began nullifYing this common law principle in the 1870s, but it has survived in American culture and in the informal culture of the criminal justice system. To take just one of thousands of examples, a New Hampshire judge, when sentencing a man who stabbed his wife, admonished him by saying-"if you had just slapped her, you wouldn't be here today" (Darts & Laurals, 1993). The multitude of ways in which the actions and inactions of the criminal justice system continued to legitimize partner assault has been documented for at least a generation (Straus, 1976). There has been remarkable progress since then, largely due to the efforts of the women's movement. Instead of advising police officers to avoid interfering in domestic disturbances, (International Association of Chiefs of Police, 1967), most police departments now require or recommend arrest (Buzawa & Buzawa, 2003; Sherman, Schmidt, & Rogan, 1992).

The reasons for the persistence of norms permitting marital violence are multiple and complex. This chapter examines the hypothesis that one of the explanations is spanking by parents. Because parents who spank or slap a misbehaving child are doing so with community approval and act in the belief that spanking is sometimes necessary for the child's own good, spanking teaches children the unintended lesson that hitting is a morally correct way of dealing with misbehavior. That lesson can then be carried over to also apply to the misbehavior of an intimate partner.

Social learning theory suggests that one of the ways children learn to use and value violence is by observing and modeling the behavior of their parents (Bandura, 1973). We think this is especially likely to happen if the violence they observe is in the form of spanking a misbehaving child because, as just noted, doing so is socially approved behavior. A 1998 survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults found that 73% believe spanking is a necessary part of child rearing (Ellison & Bradshaw, 2009). Thus, when parents spank to correct and teach, it is accompanied by an unintended hidden curriculum. One of the hidden lessons in that curriculum is that violence can be and should be used to secure good ends-that is, it teaches that violence is morally justified, not just in the extreme of self-defense, but when dealing with persistent misbehavior in ordinary human interaction (Wolfe, Katell, & Drabman, 1982). Another lesson stems from the fact that most parents hit a child only after trying other methods of correction and control. From this, children learn that violence is permissible "when other things don't work" (Straus et al., 2006, pp. 103-104).

Parents assume that these lessons about the morality ofhitting someone who misbehaves and "won't listen to reason" will be applied when their child is an adult, only to hitting a child who misbehaves. Studies of children show, however, that children who are spanked tend to apply these principles to interaction with other children who misbehave toward them (see Chapter 6 and Simons & Wurtele, 2010). This chapter builds on that research by investigating the possibility that the lessons learned persist into adulthood and dating and marital relationships. This possibility arises because it is almost inevitable that, sooner or later, a partner will misbehave and not listen to reason as the partner sees it. As one woman put it, "I punch guys for the same reasons people 'discipline' their children. I've got expectations in love, and I want him to improve" (Connell, 2002).

These research results and theories led to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: The more spanking experienced, the greater the probability of believing that there are circumstances when one would approve of hitting a partner.

Hypothesis 2: Individuals who believe that it is sometimes permissible to hit a partner are more likely to actually hit their partner than those who do not.

Truncated Development of Conflict-Resolution Skills

Another process that we investigated to try to understand what might explain why spanking is associated with an increase in physically assaulting an intimate partner starts from the assumption that the more parents rely on spanking to deal with misbehavior, the lower the child's skills will be in nonviolent problem solving. This is partly because, as was shown in Chapter 10 on spanking and cognitive ability, spanking slows cognitive development. An even more direct relationship may occur because each time parents spank, it denies the child the opportunity to observe, participate in, and learn nonviolent modes of influencing the behavior of another person. These modes include explaining, negotiating, compromising, and modifying their own behavior to adapt to the situation. As one parent we spoke to·put it, in explaining why she spanked, "I don't have time for all that." Based on this line of reasoning, we hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3: The more spanking experienced, the greater the probability of inadequate skill in managing conflict and, therefore, a higher probability of unresolved conflicts with partners.

Hypothesis 4: A high level of conflict, in turn, is associated with an increased risk of violence (as shown in Straus et al., 2006, Chart 13).

The data available for this chapter let us test the fourth hypothesis because it includes a measure of the presumed consequence of a lack of such problemsolving skills: a measure of unresolved marital conflict.

Depression

Still another process that might explain why spanking is linked to assaulting a partner identifies depression as a mediating variable (also known as an intervening variable). A mediating variable refers to a characteristic or a process that, if supported by the statistical analysis, provides at least part of the explanation for the link between the hypothesized cause variable and the effect variable.

Depression was included in the theory we tested because of the results from two related lines of research. The first line of research shows that spanking is associated with being depressed as an adult. Straus (1995a) and Straus and Kaufman Kantor (1994) found that, after statistically controlling for six risk factors (e.g., witnessing parents assault each other and a low socioeconomic status), individuals who were slapped or spanked frequently during adolescence were twice as likely to experience severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation when they were adults. There are at least 13 other studies that have found that spanking is associated with an increased probability of depression, including: Afifi et al. (2006), Bordin et al. (2009), De Vet (1997), DuRant et al. (1995), Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, (2008), Harper, Brown, Arias, & Brody (2006), Holmes & Robins (1988), Leary et al. (2008), Spencer (1999), Turner & Finkelhor (1996), Turner & Muller (2004).

A second relevant line of research has found that depression is associated with an increased probability of hostile and aggressive behavior toward others. Although depressed individuals are typically thought of as passive and motivationally deficient, a growing body of research suggests that depression is often associated with aggression, especially in the form of uncontrolled violent outbursts against others (Berkowitz, 1993). The co~occurrence of depression and aggression among children (Garber, Quiggle, Panak, & Dodge, 1991) as well as adults, led Berkowitz (1983, 1993) to speculate that depressive symptoms may be linked to hostility or violence against a partner. This speculation is confirmed by the results of studies focusing specifically on domestic violence. For example, one study found that domestically violent males are more than twice as likely (45% versus 20%) to report symptoms of clinical depression than nonviolent males (Julian & McKenry, 1993). The differences remained even when race, quality of the marital relationship, life stress, and alcohol use were controlled for statistically. Further, Maiuro, Cahn, Vitaliano, Wagner, and Zegree (1988) found that 67% of men who assaulted their wives were clinically depressed compared with 34% of young men who assaulted nonfamily members, and 4% ofnonassaultive men (see also Tolman & Bennett, 1990).

The link between depression and partner assault has not yet been adequately explained and most likely represents a complex, reciprocal relationship with· a number of other characteristics of each of the partners and of their relationship. Some researchers (Maiuro et al., 1988; Tolman & Bennett, 1990), however, have suggested that individuals who are depressed may resort to physical violence to help deal with feelings of helplessness that frequently accompany depression. In the case of marital relationships, an individual may act aggressively toward his or her partner in an effort to reestablish control over a discordant marital relationship that is in jeopardy of dissolving. Additionally, enduring patterns of low selfesteem and personal insecurity, or fears of abandonment, may predispose some individuals to respond aggressively to perceived threats of loss of the relationship.

Postulating that depression serves as a precursor to spousal aggression does not contradict the fact that depression can also be a consequence of being assaulted by a partner, as was shown by Stets and Straus (1990). We believe there is a bidirectional relationship and that depression is both a cause and a consequence of partner violence.

These theories and research results led to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5: The more spanking experienced, the greater the probability of depression.

Hypothesis 6: Depression, in turn, increases the probability of violence against a partner.

Sample and Measures

We used path analysis to test the theory that spanking is related to assaulting a partner because spanking is associated with an increased probability that the child will grow up to approve of violence, have a marriage with a high level of conflict, and be depressed. Each of these three problems, in turn, is associated with an increased probability of hitting a partner. We tested this theory separately for men and women to allow for the possibility that the effects of spanking might be different for men and women and because it is widely believed that assaults on partners by women have a different etiology than assaults on partners by men (Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Medeiros & Straus, 2006; Navaro, 1995; Straus, 2009c; White & Smith, 2009).

Sample

The sample used to test the theory consisted of 4,401 participants in the 1985 National Family Violence survey (2,557 women and 1,844 men). This sample is briefly described in Chapter 1 0 on number of children and spanking and in more detail in Straus & Yodanis (1996) and the Appendix. This is a nationally representative sample, not a sample selected because of involvement in some type of Violence. The study participants were interviewed as adults about whether they were slapped or spanked when they were adolescents. For the generation who were adults at this time of this survey in 1985, being hit when they were adolescents was far from a rare event. Just over one half of American parents at that time hit early adolescent children, and they did so an average of 8 times a year (Straus & Donnelly, 1994). The high prevalence and chronicity of corporal punishment of adolescents in this nationally representative sample is important because it indicates that, despite the fact that the data are on early adolescence, the results are broadly applicable to that generation and are not restricted to a small number of families in which there was an abnormally high level of violence.

Measures

More detailed statistical information about the following measures are in Straus and Yodanis (1996).

Corporal punishment. Corporal punishment was measured by asking each study participant, "Thinking about when you, yourself, were a teenager, about how often would you say your mother or stepmother used physical punishment like slapping or hitting you? Think about the year in which this happened the most." The response categories were never, once, twice, 3 to 5 times, 6 to 10 times, 11 to 20 times, and more than 20 times. We asked a parallel question about corporal punishment by the participant's father. Empirical research and socialization theories of parent-child relationships have noted that mothers and fathers spend unequal time, perform unique parenting roles, have different interactions, and form dissimilar relationships with their children (Demo, 1992; Peterson & Rollins, 1987). The effects of parental use of corporal punishment may also be different depending on whether it is done by the father or the mother. To find out, we examined the effects of fathers' and mothers' use of corporal punishment separately.

A limitation of this measure is that it depends on the ability and the willingness of the study participants to recall these events. Fortunately, as we noted in the previous chapter, there is empirical evidence indicating that adults' recall of events in childhood can provide a valid measure (Coolidge et al., 2011; Fisher et al., 2011; Morris & Slocum, 201 0). Further, the adult recall questions focused on adolescence because asking adults about corporal punishment at earlier ages would be less accurate. Finally, readers should note that never experiencing corporal punishment meant that it was never experienced during the teenage years; respondents could have experienced corporal punishment before they were teenagers, but that was not the focus of this question.

Assaults between partners. Assaults between partners was measured using the original Conflict Tactics Scales (described in Straus, 1979; Straus et al., 1996).

Violence approval. Violence approval was measured using two questions, "Are there situations that you can imagine in which you would approve of a husband slapping a wife's face?'' and "Are there situations that you can imagine in which you would approve of a wife slapping a husband's face?'' The response categories were 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree.

Unresolved conflict. Unresolved conflict in the respondent's marriage or other relationship was measured by questions about how often the respondent and the spouse or partner disagreed on five issues: managing the money; cooking, cleaning, or repairing the house; social activities and entertaining; affection and sexual relations; and issues about the children. The response categories were 0 =never, 1 = sometimes, 2 =usually, 3 = almost always, and 4 = always.

Depression. Depression was measured using four questions from the Psychiatric Epidemiological Research Instrument (Dohrenwend, Askenasy, Krasnoff, & Dohrenwend, 1978): "Have you been bothered by feelings of sadness or worth?," "Have you felt very bad and worthless?," "Have you had times when you couldn't help wondering if anything was worthwhile anymore?," and "Have you had times when you felt completely hopeless about everything?" Respondents were asked to report how often this happened within the past year: never= 0, almost never= 1, sometimes= 2, fairly often= 3, and very often= 4. More information about this variable can be found in Straus (1995a).

Controls

The analysis included controlling for the following factors that might influence the results: age of the participant (to control for generational differences), socioeconomic status of the ethnic group, and the witnessing of violence between parents. To make the results more readily understandable, the charts in this chapter do not include the paths from the control variables. The results for those paths and more information about the measures and statistical methods used for this chapter are in Straus and Yodanis (1996).

Interrelation of Depression, Conflict, and Approval of Violence

Up to this point, the discussion treated each of the three processes that might explain the relation of spanking to physically assaulting a partner separately. However, attitudes about the legitimacy of hitting a partner, conflict resolution skills, and depression are likely to work together to increase the likelihood of partner assault. This perspective is based on research showing that marital conflict and depression are linked (Beach, Sandeen, & O'Leary, 1990; Julian & McKenry, 1993; Maiuro et al., 1988). As for links with approval of violence, although we have not found previous research showing a connection between approval of violence and marital conflict and depression, such a connection is plausible as the cognitive aspect of the link between marital conflict and depression. The results of examining the relation of these mediating variables to each other revealed the following:

* Depression and marital conflict. Women with a high level of depression were about 3.4 times more likely to have a high level of marital conflict, and men with a high depression score were about 2.5 times more likely to be in a relationship with a high level of conflict. It is important to keep in mind that, because this is a cross-sectional study, it is just as plausible to interpret this result as showing that a high level of conflict is associated with an increased probability of depression, or that there is a bidirectional relationship and perhaps also an escalating cycle.

* Depression and approval of marital violence. Women with a high depression score were 1.7 times more likely to approve of marital violence. For men, there was no relationship between depression and approval of hitting a partner.

* Marital conflict and approval of marital violence. Men who approved of slapping a partner under some circumstances were 2.5 times more likely to be in a relationship characterized by high levels of conflict. For women, there was no relationship between conflict and approval of hitting a partner.

The difference between the findings for men and women might reflect gender differences in socialization and conflict management. To be more specific, these fmdings may reflect the tendency of men to externalize problems in the form of aggression and of women to internalize problems in the form of depression (Kramer, Krueger, & Hicks, 2008; Maschi, Morgen, Bradley, & Hatcher, 2008).

Relationship Between Spanking and Assaulting a Partner

The arrows in Chart 12.1 show the connections between the variables that were found to be statistically dependable. The numbers on each of these paths indicate the percent by which an increase of one unit of the variable at the start of the path is associated with an increase or decrease in the probability of the variable at the end of the path. The detailed tests of significance are in Straus and Yodanis (1996).

Chart} 2.1 Three of the Processes Explaining the Link between Spanking and Assaulting a Partner

Direct Links between Spanking and Assault

Spanking by mothers. The upper section of Chart 12.1 (Part A) summarizes the results for assaults by male partners, and the lower section (Part B) summarizes the results for assaults by female partners. In the chart for assaults by men, the 9% on downward sloping arrow in the middle that goes from Spanking by Mother on the left to Assault by Husband on the far right indicates that each increase of one category in the seven-category measure of having been spanked or slapped by a mother is also associated with a 9% increase in the odds of a man assaulting his partner. The comparable arrow in Part B (the lower half of Chart 12.1) shows the same link between spanking or slapping by mothers and women assaulting their male partners.

Spanking by fathers. The results for Spanking by Father in Part A does not show a direct path from Spanking by Father to Assault by Husband because a statistically dependable relationship was not found. On the other hand, the chart for women (Part B) does show a direct path from Spanking by Father to Assault by Wife. The arrow from Spanking by Father to Assault by Wife shows that for each increase of one category in the spanking or slapping scale, there is an 8% increase in the probability of a woman physically assaulting her partner. In short, spanking or slapping by a mother is associated with an increased probability of later hitting a partner for both men and women, but spanking or slapping by a father is only related to women hitting their partner. However, as will be shown in the n'ext section, spanking has similar indirect effects leading to physical assaults against a partner by both men and women.

The Mediating Mechanisms

The main issue addressed by this study is the theory that part of the explanation for the link between spanking and assaulting a partner is that spanking increases the probability of depression, approval of violence, and marital conflict. The paths from having been spanked or slapped to these three variables in the middle of both Part A and B of Chart 12.1 show the results of investigating three processes that might explain why being spanked or slapped by parents is associated with assaulting a partner.

Depression. One hypothesized process that might help explain the link between having been spanked or slapped by parents and physically assaulting a partner is that spanking or slapping increases the probability of depression. The paths from Spanking to Depression in both parts A and B of Chart 12.1 show that, for men and for women, the more spanking by mothers, the more likely both men and women are to have symptoms of depression. For women, but not for men, this also applies to spanking by fathers. The 193% on the path from Depression to Assault in Part A of Chart 12.1 shows that men in the highdepression group were almost 3 times more likely to have assaulted a partner in the previous 12 months than other men. The same path in Part B of Chart 12.1 shows that women in the high-depression group were just over twice as likely (107% increase) to have physically assaulted a partner than were other women.

Approval of violence. Another process that might explain why spanking is associated with an increased probability of assaulting a partner is that spanking increases the probability of approving violence. For this study, that was measured by whether the study participant agreed that there are circumstances when they might approve of a husband slapping his wife and a wife slapping her husband. Because a central theme of this book is that spanking is a fundamental cause of violence in the family and in society, we graphed that relationship in detail. Chart 12.2 shows that spanking or slapping is related to approval of violence by men, even when there was no violence between their parents as well as when there was. This does not mean that witnessing assaults between parents is unimportant. The fact that the line for men who witnessed this type of violence is higher on the graph shows that witnessing violence is also associated with even more approval of violence. Men who both witnessed physical assaults between their parents and were hit by their parents as an adolescent have the highest level of approving a husband slapping his wife. Almost identical results were found for women.

Returning to Chart 12.1 in Part A, there are paths on this issue for Spanking by Father and for Spanking by Mother. For men, the 11% on the path going from Spanking by Mother to Approval of Violence indicates that each increase of one point on the seven-point spanking or slapping scale is associated with an 11% increase in the probability of approving a husband slapping his wife. The 8% on the path from Spanking by Father to Approval of Violence shows that each increase of one unit in the measure of having been spanked or slapped as a teenager is associated with an 8% increase in the probability of approving the slapping of a partner. Part B of Chart 12.1 shows that for women, spanking by mothers, but not spanking by fathers is associated with a greater probability of approving a wife slapping a husband. For women, the 13% on the path in Chart 12.1 from Spanking by Mother to Approval of Violence indicates a somewhat stronger tendency for spanking or slapping by a woman's mother to be linked to approving slapping a husband. However, for women, we did not find a statistically dependable relationship between Spanking by Father and Approval of Violence. For women, spanking by fathers was related to an increased probability of depression.

Chart 12.2 The More Spanking Men Experienced, the Higher the Probability They Will Approve of a Husband Slapping His Wife

* "Approve" was measured as the percent who did not strongly disagree that "I can think of a situation when I would approve of a husband slapping a wife's face."

The paths in Part A going from approval of violence to assault shows that men who agreed there are circumstances when they would approve of a husband slapping his wife are about twice as likely to actually hit their partner than are other men. Similarly, Part B shows that women who agreed that there are circumstances when they would approve of a wife slapping her husband were about twice as likely ( 109% increase) to have physically attacked their partner in the previous 12 months. These findings are consistent with the theory that spanking teaches the moral legitimacy of hitting someone who misbehaves, and this in turn increases the probability of actually physically assaulting a partner who misbehaves as that partner sees it.

Marital conflict. The paths from Spanking by Mother to Marital Conflict in Parts A and B of Chart 12.1 show that the more spanking by mothers, the more likely both men and women are to report high marital conflict. However, there is no path from Spanking by Father to Marital Conflict because we did not find a statistically dependable relationship for this path. The paths from Marital Conflict to Assault in both Parts A and B of Chart 12.1 show that high marital conflict was associated with men being 164% more likely to assault a partner and women being 243% more likely to assault a partner. These results are consistent with the theory that spanking and assaulting a partner are related because spanking restricts a child's opportunity to learn nonviolent modes of conflict resolution and, therefore, increases the probability of a high level of marital conflict, which in tum is associated with an increase in the probability of physically attacking a partner.

Do the Results Apply to Severe Assaults?

We also investigated the possibility that the results just presented might be different if the outcome variable was severe assaults; that is assaults involving attacks with objects, punching, and choking. These are acts, such as kicking and punching, that are associated with a greater risk of causing injury than slapping, shoving, and throwing things (see Straus & Yodanis, 1996), for information on the severe assault scale.) The results for severe assaults were similar to those just reported. The analysis for men found that depressive symptoms, violence approval, and marital conflict were associated with an increased probability of severely assaulting a female partner. Spanking or slapping by mothers, however, was not associated with severe assaults by men. The analysis for women found that depressive symptoms, violence approval, marital conflict, and spanking by mothers were associated with an increased probability of severely assaulting a male partner. Spanking or slapping by the fathers of these women, however, was not associated with an increased probability of severe assaults by women. Other Variables Related to Assaulting a Partner

The five variables included in the analysis as controls are also of interest in their own right. The tables in Straus and Yodanis (1996) show that:

* Having grown up in a family where there was violence between their parents was associated with an increased probability of depression, approval of slapping a partner, marital conflict, and actually assaulting a partner.

* The probability of approving violence and actually assaulting a partner decreases with age. This is consistent with other studies of crime, including assaulting a partner (Suitor, Pillemer, & Straus, 1990).

* Higher socioeconomic status was associated with a lower probability of both the men and women in this study, being high in depression, approving the slapping of a partner, experiencing marital conflict, and actually . assaulting a partner.

* Minority ethnic group respondents in this study had a higher probability of marital conflict and assaulting a partner.

Summary and Conclusions

This chapter tested a theory about some of the processes that bring about a link between spanking and physically assaulting a partner in a marital or cohabiting relationship. The processes investigated are three of the adverse side effects of spanking: depression, attitudes approving violence, and marital conflict (which we used as proxies for deficits in conflict-resolution skills resulting from the use of corporal punishment). Our theory is that spanking is associated with an increased probability of each of these, and each in turn is associated with an increased probability of assaulting a partner. The results of the analyses from a nationally representative sample of married or cohabiting partners were largely consistent with this model. We found that spanking in adolescence was associated with an increased probability of:

* Experiencing depression as an adult

* Approving violence against a spouse

* A high level of marital conflict

In turn, each of these effects of spanking was associated with an increased probability of physically assaulting a partner. Thus, at least part of the association between spanking and adult spousal assaults is explained by these three variables. Moreover, these links were found for both men and women regardless of age, socioeconomic status, ethnic group, and whether or not the participants in the study grew up in a family in which there were assaults between their parents. Thus, spanking had a unique effect that was in addition to the effect of the control variables.

The Dose-Effect of Spanking

Defenders of spanking believe it is not harmful if it is used only rarely. To address this, we examined differences between participants in this study who were never hit, hit only once, hit only twice, hit 3 times, etc. Those analyses showed that each increase in spanking of an adolescent, starting with just one instance, was associated with an increase in approval of violence and actual violence toward a partner. Harmful effects for rare spanking are shown in the chapters on spanking and children's antisocial behavior, the outcomes associated with impulsive spanking (Chapters 6 and 7), and the other four chapters in this part of the book and in Straus (1994, Chart 7-2, 2001a) and in a study by Turner and Finkelhor (1996). Turner and Finkelhor used data from interviews with children age 10 to 16. They found that even one or two instance of spanking at those ages was associated with an increase in stress in children.

Some Limitations

Although the analysis controlled for a number of possible sources of spurious findings, some limitations of the research need to be considered to properly evaluate the findings. First, the effect of spanking might have occurred because some of the participants who experienced spanking might also have experienced more serious violence in the form of physical abuse. If so, that probably accounts for part of the effects on the participants who experienced frequent spanking. It is unlikely to explain the effects of low and moderate amounts of spanking because those participants were unlikely to have been victims of more severe physical attacks. In addition, s.tudies by MacMillan et al. (1999); Straus and Kaufman Kantor (1994); Straus and Donnelly (2001a); Vissing et al. (1991); and Yodanis (1992) were able to exclude abused childfen and, after excluding them, each of those studies found that spanking continued to have significant harmful side effects such as those reported in this chapter.

Another limitation is that the spanking data were obtained by asking the study participants about being hit by their parents when they were adolescents. This raises several problems. Those who were hit at that age might be an unrepresentative sample. However, as reported earlier, more than half of the cohort in this study recalled being hit at the age. Thus, corporal punishment of early adolescents was typical of the U.S. population of that time. Since then, the percent of early adolescent children who are slapped or spanked has decreased. The data are, therefore, dated in respect to the prevalence of spanking, but as we pointed out earlier, this does not necessarily affect the relationship between spanking and later assaulting a partner. Another problem is that adults' recall data can be biased. However, it is not necessarily biased, as shown by studies such as (Coolidge et al., 2011; Fisher et al., 2011; Morris & Slocum, 2010). Nevertheless, participants in the study who hit their partners might perceive and report their parents as more violent than those who did not assault their partner. Although that is a concern for the study in this chapter, there are studies that do not depend on recall. These include the chapters on spanking and child behavior (Chapter 6), impulsive spanking (Chapter 7), the child-to-mother bond (Chapter 8), and spanking and adult crime (Chapter 15). Strassberg et al. (1994), Gershoff et al. (2010), and Taylor et al. (2010) all found that spanking is associated with subsequent violence. It is unlikely that, 20 years later, the study participants can accurately recall how many times they were hit. As a consequence, we view this as an ordinal measure that indicates who was hit more than others, not a measure of the actual number of times. Finally, most of those who were not spanked in their early teenage years were probably spanked at earlier ages. Thus, the results do not refer to those who were spanked and those who were not. They mostly refer to those for whom spanking continued into the early teenage years. One implication of this limitation is that the results shown may be minimum estimates of the effects of spanking because the most : of the group who were not spanked in their early teenage years experienced the spanking earlier.

Finally, this was not a longitudinal study that controlled for misbehavior that led to the spanking. As a consequence, unlike the three longitudinal studies in this book and the longitudinal studies listed in Chapter 19 on spanking and its implications for societal-level crime and violence, the relationships found may reflect the effects of the maladaptive characteristics of the study participants who hit their partner, rather than the effects of spanking.

Policy Implications

To the extent that these cross-sectional findings can be interpreted as reflecting a causal relationship between spanking and assaulting a partner later in life, eliminating or reducing spanking can contribute to reducing marital violence. This is because, although spanking has declined in the United States, at least one third of American parents continue to hit early adolescent children (see Chapter2).

Reducing or ending spanking may also make an indirect contribution to ending marital violence through its effect on the way the criminal justice system deals with partner violence. Police and prosecutorial policies intended to reduce partner violenc~ have often been weakly implemented (Garner & Maxwell, 2009). It is possible that the link between spanking and approval of slapping a partner may be one of the factors underlying this weak implementation. The attitudes of police, prosecutors, and judges, like most other Americans, may reflect violence-justifying effects of spanking. That may be part of the reason the criminal justice system so often fails to act against all but the most egregious cases of marital assault. To the extent that criminal prosecution in cases of partner violence is an effective policy, ending spanking in child rearing could contribute to ending the de facto institutional practices that tolerate violence between marital, cohabiting, and dating partners.

The results in this chapter also suggest that a reduction in spanking could have a beneficial impact on one of the most pervasive forms of psychological distress-depression. Close to 15% of the population will experience an episode of major depression at some point in their lives (Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, 2005). Moreover, mood disorders account for more usage of mental health services than any other psychiatric disorder and are responsible for the majority of all attempted and completed suicides (Boyer & Guthrie, 1985; Charney & Weissman, 1988). Thus, in addition to the association of spanking with physical assaults, the severity of the consequences associated with depression also underscores the need for professionals working with parents (such as nurses, parent educators, and pediatricians), to inform parents about the harmful side effects of spanking and help them avoid using spanking.

13 Assault and Injury of Dating Partners by University Students in 32 Nations

The previous chapter showed that spanking is associated with an increased probability of physically assaulting a partner. It also provided information on some of the processes or mechanisms that could explain why spanking is related to assaulting a partner among couples in a large and nationally representative of U.S. households. The research described in this chapter extends the examination of the link between spanking and assaulting a partner by examining these questions:

* What percent of university students in 32 nations physically assaulted a dating partner in the previous year?

* Does the link between spanking and physically assaulting a partner found for U.S. couples in the previous chapter apply to dating relationships of university students in 32 nations?

* What is the effect of being in these 32 different national social contexts on the prevalence of attitudes favoring slapping a partner and actually assaulting a partner, and the relationship of spanking to those attitudes and behaviors? That is, when the percent of the students in a national context who were spanked a lot is large, is there a correspondingly large perpent of students who:

• Approve of slapping a partner? • Actually assaulted a partner? • Injured a partner?

Information on the extent to which physical violence in university student dating relationships result in physical injury is important because we think that many people believe that acts of violence between dating couples is rarely serious or dangerous.

Emily M. Douglas is the first author of this chapter.

National Differences in Dating Partner Violence

There is an important difference between this chapter and the previous chapter in the method of research. This chapter presents the results of a cross-national comparative study in which the issue is the potential effect of the national context on violence in couple relationships. To do this, we used data on the percent in each of the 32 nations of university students who experienced corporal punishment and the percent in each nation of students who had attitudes favorable to hitting a partner under certain circumstances, the percent in each nation who actually assaulted a partner, and the percent who assaulted seriously enough to physically injure their partner. The underlying theoretical reason for the focus on nations is to find out if social settings where there is a high rate of violent socialization of children in the form of spanking also tend to be social settings where there is a high rate of physically assaulting a dating partner.

Assaults on Dating Partners

Student Rates versus General Population Rates

As high as the percent of married couples who engage in physical assaults is (see previous chapter), numerous studies have found even higher high rates of physical assault on dating partners by university students. The typical results show that from 20% to 40% of students physically assaulted a dating partner in the previous 12 months (Archer, 2000, 2002; Katz, Washington Kuffel, & Coblentz, 2002; Sellers, 1999; Sugarman & Hotaling, 1989). The dating couple rates are 2 to 3 times greater than the rates typically found among representative samples of American households, and both the household and the dating couple assault rates are many times the rate of assaults known to the police. Assaults known to the police are reported as rates per 100,000 population, whereas assaults between couples are so prevalent that percentages (the rate per 100 couples) are more appropriate.

The much higher rate of assault by university students than in surveys of households is probably because most students are much younger. The average age of university students is about 20, whereas the average age of community samples of couples is about 40. The long established age-crime curve refers to the fact that most crimes, and especially violent crimes, peak in the late teens or early twenties and then decline rapidly. That is clearly the case for the crime of assaulting a partner. The rates decline from a peak of over 30% for the late teens to less than one half that at about age 40 (Straus & Ramirez, 2007; Suitor et al., 1990). Most of the dating violence studies have been in the United States and Canada. As noted previously, one of our objectives was to determine the extent to which these monumentally high assault rates are found among students in other national settings around the world. If high rates of physical assaults against dating partners are found to be characteristic of university students in most or many countries, it adds urgency to research which can help explain why so many students engage in this type of behavior.

Hypotheses

Like any form of violence, assaulting a partner has multiple causes. For purposes of this book, we investigated whether the prevalence of corporal punishment is one of them. The specific hypotheses we tested are:

The higher the percentage of students in a nation who are spanked as children, the higher the percent of students who:

* Approve of a husband slapping his wife and a wife slapping her husband * Assaulted a dating partner * Injured a dating partner

Sample and Measures

Sample

The hypotheses were tested using data on assaults perpetrated against dating partners by university students who participated in the International Dating Violence Study in 32 nations. The study and the sample are described in Chapter 3 on the worldwide prevalence of spanking and in (Rebellon et al., 2008; Straus, 2008b, 2009b). We analyzed data on the 14,252 ofthe 17,404 students in the study who were in a romantic relationship. Of the 32 nations, there were two in Africa, seven in Asia, thirteen in Europe, four in Latin America, two in the Middle East, two in North America, and Australia and New Zealand.

Measures

Spanking. Spanking was measured by asking the students whether they agreed or disagreed that: "I was spanked or hit a lot by my parents before age 12" and "When I was a teenager, I was hit a lot by my mother or father." The response categories were: strongly agree (1), agree (2), disagree (3), and strongly disagree (4). Anyone who did not strongly disagree was considered to have been spanked as a child. This is based on assuming that if their parents had not spanked or hit a lot they would choose strongly disagree. We tested that assumption before proceeding by computing the correlations of these variables with approval of a husband hitting his wife under some circumstances. Each pair of correlations compared counting anyone who chooses any response, except strongly disagree, as having been spanked with correlations using agree or strongly agree as the criterion. All the correlations were higher using not strongly disagree as the criterion for having been spanked.

The question asks about being spanked or hit a lot because of evidence that a lot is the typical experience in the United States, and perhaps in most of the other nations in the study. Studies that measured how often toddlers were hit have found an average to 2 to 3 times a week (Giles-Sims et al., 1995; Holden et al., 1995; Stattin et al., 1995). One study found that even at age 6, 70% of children were hit once a week or more (Vittrup & Holden, 2010).

Approval of partner violence. Two questions were used to measure approval of violence against a partner: "I can think of a situation when I would approve of a husband slapping a wife's face" and "I can think of a situation when I would approve of a wife slapping a husband's face." The response categories for these questions were the same as for the spanking question. The cut points were again the percentage of students at each nation who did not strongly disagree. And again, exploratory analyses found stronger correlations using this cut point than with other possible cutting points.

Measures of partner violence. Physical assault and injury were measured by the revised Conflict Tactics Scales or CTS2 (Straus et al., 1996). In the past 25 years, the Conflict Tactics Scales have been used in hundreds of studies in many nations, but especially in economically developing nations because it is part of the World Health Organization sponsored studies of maternal health. It has demonstrated cross-cultural reliability and validity (Archer, 1999; Straus, 1990a, 2004; Straus & Mickey, 2012). For this chapter, we used the CTS2 scales measuring physical assault and physical injury, and the subscales for severe assault and severe injury. As in previous studies using the CTS with general population samples, most of the assaults and injuries were in the minor category. Because severe violence may be a unique phenomenon with a different etiology, (Straus, 1990c; Straus, 2011; Straus & Gozjolko, in press) all analyses were conducted for the overall rates of partner violence, and then repeated for the rates of severe violence.

Physical assault. The CTS2 uses five behaviors to measure minor assault, for example, slapping a partner. For severe assault, there are seven behaviors, for example, punched or choked a partner. The overall rate of partner assault is the percent in each nation who perpetrated any one or more of the 12 acts.

Injury. There are five CTS2 items to measure injury inflicted on a partner, such as "Having a sprain, bruise, or cut after a fight with a partner" (a minor injury item) and "Needed to see doctor because of a fight with a partner." The scales for assault and injury were coded 1 if any of the acts occurred in the past year and coded 0 if there were none. The data used for this chapter are the percentage of students at each nation with a score of 1, which is the percentage who assaulted or injured a dating partner. The reliability for the overall physical assault scale for the samples in this study was .88. For the injury scale, the alpha coefficient was .89.

Moderator and control variable. Because the etiology and the effects of assaulting a partner may be different for men and women, we used gender as a moderator variable by repeating all analyses for male and female students.

The analysis controlled for the score for each nation on the limited disclosure scale (Chan & Straus, 2008; Sabina & Straus, 2006; Straus et al., 2010; Straus & Mouradian, 1999). In research on self-reported criminal behavior, differences between nations could reflect differences in the willingness of people in different nations to report socially undesirable behaviors and beliefs as much or more than real differences in crime and criminogenic beliefs. For example, we found that the higher the score on the limited disclosure scale, the lower the percent who agreed that they could think of a situation when they would approve of a husband slapping his wife (r = -.36) and the lower the percent who said they had injured a partner (r = -.21). Scores of the students in each nation on the limited disclosure scale permit a statistical control for nation to nation differences in willingness to disclose such information. Without this control, the results could be spurious; that is, the correlations might reflect differences between nations in the willingness of students to self-report socially undesirable behavior and beliefs rather than differences in spanking.

Data Analysis

The analyses used a nation-level data file, in which the cases are the 32 nations, not individual students. The data for each case consists of summary statistics for the nation, such as the mean or the percentage of students with a certain characteristic. Separate data files were created for males and females, based on aggregating the data for the males and females in each site, and the analyses were replicated using those files.

Partial correlation analysis was used to test the hypothesized relationships of corporal punishment to approval of slapping a spouse, perpetration of physical assault against a dating partner, and injuring a dating partner. The analyses controlled for the age of the respondent, length of the relationships,· social desirability, and socioeconomic status-and for analyses of the total sample, gender of the respondent.

Differences Between Men and Women and Between Nations

This section describes the percent of students at each of the 32 nations who were spanked as a child and as a teenager, the percent who approved of violence against a dating partner, and the percent who physically assaulted and injured a dating partner in the previous 12 months. For each of these beliefs and behaviors, we give the average percentage for all32 nations, and also the nation with the lowest and the highest percent and the percent for the United States. The section below on differences between nations explains how to use Charts 13.2 to 13.7 to get a rough estimate of the percentages for each nation, and for men and women students.

Spanking before age 12. The percent of students who were spanked as a child ranged from 15% in the Netherlands to 75% in Taiwan. The average for the 32 nations was 47%. Table 2 in Chapter 3 and Chart 13.2 give the percent for each of the 32 nations and also show that in almost all nations, boys were hit somewhat more than girls.

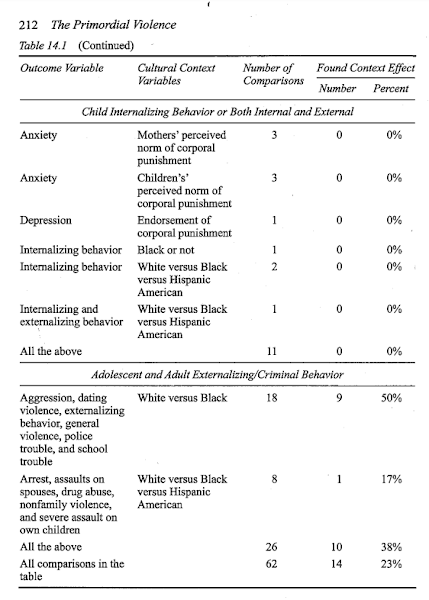

Chart 13.1 Nations Where Students Have Experienced More Spanking Tend to Also Be Nations Where a Larger Percent of Students Approve of Partner Violence, Assault a Partrler, and Injure a Partner"

• M = Correlation for male student data. F = correlation for female student data.

*p < .05, **p < 01. Coefficients on each line are the partial correlations using nations as the cases (N = 32), controlling for mean limited disclosure scale score of each nation.

Chart 13.2 The Larger the Percent in a Nation Who Experienced Spanking as a Child, the Larger the Percent Who Approved a Husband Slapping His Wife

Chart 13.3 The Larger the Percent in aN ation Who Experienced Spanking as a Child, the Larger the Percent Who Approved a Wife Slapping Her Husband

Chart 13.4 The Larger the Percent in a Nation Who Experienced Spanking as a Child, the Larger the Percent Who Assaulted Their Partner

Chart 13.5 The Larger the Percent in a Nation Who Experienced Spanking as a Child, the Larger the Percent Who Severely Assaulted Their Partner

Chart 13.6 The Larger the Percent in a Nation Who Experienced Spanking as a Child, the Larger the Percent Who Injured Their Partner

See Chart 3.2 for the key to nation abbreviations.

Chart 13. 7 The Larger the Percent in a Nation Who Experienced Spanking as a Child, the Larger the Percent Who Severely Injured Their Partner

See Chart 3.2 for the key to nation abbreviations.

The 47% who experienced spanking as a child, as reported by the students in this sample, is almost certainly an underestimate for the children and families from the nations in this study. Among the U.S. students, for example, only 61% reported spanking before age 12, whereas Chapter 2 on spanking in the United States shows that 94% of the parents interviewed reported spanking toddlers at least once in the preceding year. The difference between 94% and 61% probably reflects at least three things. First, many people cannot remember much of what happened when they were toddlers (the peak ages for spanking). Second, the question asked about being spanked a lot, whereas the percent in Chapter 2 is for any spanking in the previous 12 months. Third, this is a sample of university students and, therefore, has relatively few from the lowest socioeconomic status households where spanking is most prevalent. These reasons for underestimating probably apply to students in all 32 nations. To the extent that the underestimate applies to all the nations, it means that the percentages can be used to rank the percent of students in the 32 nations who were spanked. That rank order is crucial for determining if the extent of spanking in a national context is associated with the percent who assaulted.

Teenagers. We had expected the percent of students who were hit as teenagers would be substantially lower than the percent who were spanked before age 12, in part because that is what our three national surveys of parents in the United States have found (see Chapter 2). However, the percentages for the university students in this sample are lower, but not that much lower. They ranged from 10% hit as a teenager in the Netherlands to 66% in Tanzania, with the average for the 32 nations being 33%. This is lower than the 44% for being hit before age 12, but not nearly as much lower as we expected. As we found for being hit before age 12, the percent of boys in each nation who were hit by parents as a teenager was almost always slightly higher than the percent of girls who were hit as a teenager (see Chapter 3, Table 3.2).

Approval of husband slapping his wife. The students were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with "I can think of a situation when I would approve of a husband slapping a wife's face." The percent who did not strongly disagree that they could approve of a husband slapping his wife in some situations ranged from 28% in the Netherlands to 85% in Russia. The average for the 32 nations was 51%. Among U.S. students, 38% did not strongly disagree that they could approve of a husband slapping his wife in some situations.

Approval of a wife slapping her husband. The students were also asked the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with "I can think of a situation when I would approve of a wife slapping a husband's face." The percent who did not strongly disagree that they could approve of a wife slapping her husband in some situations ranged from 59% in Japan to 96% in Russia. The median for the 32 nations was 77%. Among U.S. students, 77% did not strongly disagree that they could approve of a wife slapping her husband in some situations.

The much higher percent of students who would approve of a women slapping her husband in some circumstance (median of 51%) than approve of a man slapping his wife (median of 77%) is consistent with several other studies (Felson, 2000; Felson & Feld, 2009; Gulas, McKeage, & Weinberger, 2010; Nabors, Dietz, & Jasinski, 2006; Simonet al., 2001; Sorenson & Taylor, 2005; Straus, 1995b; Straus, Kaufman Kantor et al., 1997). It is an indication of cultural toleration of a woman hitting her partner. Part of the explanation is probably public recognition of the greater potential for injury when men assault women (Greenblat, 1983). Regardless of why assaults by women are more accepted, that cultural acceptance is probably also one of the reasons that more than 200 studies have found higher rates of assault by female than male partners (Archer, 2002; Fiebert, 2010; Straus, 2008b, 2009c). Of course, many other variables also contribute to the high rate of assaults by women on male partners, for example, women are protected (up to a certain point) by chivalry norms (Felson, 2002; see also Straus, 1999; Winstok & Straus, 2011a).

Differences between nations. The approximate values for each nation of the variables in this study can be found by reading the values shown on the vertical and horizontal axes in Charts 13.2 to 13.7. For example, in Chart 13.2, the plot point for Israel (ISR) in the lower left of the panel for men shows that 33% of the male students in Israel did not strongly disagree that "I can think of a situation in which I would approve of a husband slapping a wife'sface." On the other hand, when it comes to a wife slapping her husband, the plot point for Israel in Chart 13.3, shows that almost twice as many of the men (63%) did not strongly disagree that there are situations in which they might approve of a wife slapping her husband. As pointed out earlier, greater acceptance of a wife slapping her husband than the husband slapping his wife is consistent with several other studies.

Assaulting a partner. The percent who physically assaulted a partner in the previous 12 months differed greatly from nation to nation. For all assaults regardless of whether it was a minor assault like slapping or a severe assault like punching, the rates ranged from 17% in Portugal to 40% in Iran, and the average for the 32 nations was 30%. A rate in the range of20% to 40% is typical of most studies of dating partner violence (Archer, 2002; Katz et al., 2002; Stets & Straus, 1990; Sugarman & Hotaling, 1989). Even the lowest assault rate in this study is still very high, compared with rates for other nonclinical populations. For example, it is about 3 times higher than the percent of married and cohabiting couples who physically assault (Gelles & Straus, 1988; Straus & Gelles, 1986; Straus & Smith, 1990).

Our finding that, in most of the 32 nations, female students were somewhat more likely than male students to have assaulted a partner is also typical of other studies of university students (Archer, 2002; Desmarais et al2012; Straus, 2008b ). The percent of male and female students in each nation who assaulted a partner in the previous 12 months is given in Straus (2008b) and can also be determined by reading the value for a nation in the vertical axis of Chart 13.6.

For severe assaults, the rates are of course much lower. The percent who severely assaulted a partner in the previous 12 months ranged from 1.8% in Sweden to 22% in Taiwan, and the average for the 32 nations was 11%. Among U.S. students, 11% reported severely assaulting a partner. Considering that these are severe assaults (roughly analogous to an aggravated assault in the U.S. legal system), these are extremely high rates.

Injured a partner. Although in this and more than 200 other studies (Desmarais et al2012; Fiebert, 2010), as many or more female than male students assaulted a partner, the attacks by male students usually resulted in more injury than attacks by female students (Archer, 2000, 2002; Capaldi et al., 2009; Whitaker, Haileyesus, Swahn, & Saltzman, 2007). The typical finding is that women suffer about two thirds of the injuries. However, for this study, as in a few other studies, the difference was much smaller. The 6.9% of female students who were injured is only 15% higher than the 6.0% of male students who suffered an injury from an attack by a female partner. The results for severe injury show a larger difference: 1.6% of the women suffered a severe injury compared with 1.1% of the men, which is a 45% higher injury rate for women. For the U.S. part of the sample, the rates for any injury of students are 7.8% of women and 7.6% of men, which is only a 3% difference. For severe injury however, the rate of injury of U.S. women students was 46% greater than the rate of severe injury of male students (1.9% of women, 1.3% of men). These injury rates are roughly consistent with the rates for a nationally representative sample ofU.S. couples (Stets & Straus, 1990).

Relationship between Spanking and Partner Violence

As astonishing and important as are the high percent of university students who approve of slapping a partner under some circumstances, and who actually assaulted a partner or inflicted injury, the crucial issue for this chapter is why these aspects of violence are so prevalent. Of course, there are many forces at work. The one we investigated for this book is whether nations in which spanking is more prevalent also tend to be nations in which there is a high rate of approving of slapping a partner and actually assaulting and injuring a partner. To find out, we computed the correlation of the level of spanking in each nation with each of the six aspects of partner violence described above, again, by nation, controlling for the score on the limited disclosure scale. The correlations are shown in Chart 13 .1. Most of these correlations are large enough to be, statistically dependable despite being based on only 32 cases. Because the link between having been spanked and assaulting a partner might be different for men and women, we ran the analysis separately for male and female students. In addition, the analysis controlled for nation-to-nation differences in reluctance to disclose socially undesirable beliefs and behaviors. Chart 13.1 summarizes what we found in the form of the correlations between spanking and each of the six aspects of partner violence studied. Charts 13.2 to 13.7 are scatter plots with the regression line showing the relation of the percent spanked in each nation to each of the six aspects of violence. They also indicate (with the aid of a ruler), the percentages for each of the 32 nations for each of these aspects of violence, separately for men and women. See the example presented earlier in the section on differences between nations.

Spanking before Age 12

The correlation coefficient of .57 on the top arrow in Chart 13.1 shows that the larger the percent of male students in a nation who were spanked or hit a lot before they were 12, the larger the percent who did not strongly disagree with the statement "I can think of a situation when I would approve of a husband slapping a wife's face." The correlation of .42 on that line is for women. It shows almost as strong a relationship between being spanked as a child and approval of a husband slapping his wife. Chart 13.2 lets the reader see which nations are low and high on spanking and approval of a husband slapping his wife. The trend line shows that the higher the percent of students in a nation who were spanked or hit a lot before they were 12, the higher the percent who approved of a husband slapping his wife under certain circumstances, and that this applies to both men (the left side of the chart) and women (the right side of the chart).

Spanking during the Teenage Years

The correlations on the underside of the top arrow in Chart 13.2 are for teenag _ ers. For men, the correlation of .53 is almost as strong a relationship to approval of a husband slapping his wife as was found for being spanked as a young child. For the women in this sample, however, the correlation of .28 is not large enough to be statistically dependable when there are only 32 cases.

In Chapter 5 on approval of violence and spanking, we presented similar results, but for that chapter, the focus was on whether people who approve of slapping a wife are more likely to approve of spanking. We believe both are correct-that is, that spanking increases the probability of being inclined to violence (our interpretation of the results in this chapter) and that being inclined to violence increases the probability of spanking (our interpretation of the results in Chapter 5).

Spanking and Approval of a Wife Slapping Her Husband

The correlations on the top of and below the arrow leading to Approve of Slapping by Wife in Chart 13.1 show that the only statistically dependable result we found for the issue of whether spanking is related to approval of a wife slapping her husband was for women who were spanked or hit a lot before they were 12 years old. Even that correlation is smaller than the correlations for approval of husband slapping a wife. This was unexpected because, as shown earlier in this chapter, a larger percent of the students approved of a wife slapping "her husband. Although only one of the four relationships is statistically dependable, the percent of men and women students in each nation, who approved of a wife slapping her husband under certain circumstances, are important descriptive statistics.

Spanking and Assaulting a Partner Any assault. The percentages of men and women who assaulted a partner are given in Chart 13 .4. The arrows leading to Assault in the center of Chart 13.1 give the partial correlations from testing the hypothesis that the higher the prevalence of spanking in a nation, the more likely students would be to physically assault a dating partner. Contrary to what we expected, for men we found no relationship between the percent in a nation who were spanked and physically assaulting a partner. However, for women, the larger the percent in a nation who experienced spanking, the larger the percent who physically assaulted a partner.

Severe assault. Most of the assaults in the Assault measure are minor, such as slapping or throwing something at a partner. Because severe violence may be a unique phenomenon with a different etiology (Straus, 1990c; Straus, 2011; Straus & Gozjolko, in press), we repeated the analysis using severe assaults such as punching and choking a partner. The correlations on the arrows to Severe Assault against Partner are all large and statistically dependable. Thus, for both men and women, the percent in a nation who were hit by parents to correct misbehavior, either as a child or as a teenager, is related to an increased percent in who severely attacked a partner. Again, the link between spanking and severe assault on a dating partner is slightly stronger for the women in this study than for the men. The percentage in each nation who severely assaulted a partner in each nation is indicated in the vertical axis of Chart 13 .5. See the example for Israel of how to find these percentages in the charts given in a previous section on differences between nations.

Spanking and Injuring a Partner

Any injury. Charts 13.6 show the percentages in each nation who injured a partner. The arrow leading to Injury in the lower part of Chart 13.1 shows that the larger the percentage of students in a nation who experienced spanking as a child, the higher the percentage who injured a dating partner. This relationship applies to both male and female students when the outcome variable is any injury.

Severe injury. When the outcome variable is severe injury to women, the results, are similar in the sense that all four of the correlations are in the predicted direCtion, but only the correlation of .63 for the relation of corporal punishment as a teenager to severely injuring a partner is large enough to be statistically dependable. Although the correlation of spanking before age 12 with severely assaulting a partner is not strong enough to be statistically dependable, we included Chart 13.6 (the scatter plot for this relationship) because it shows the approximate percent of students in each of the 32 nations who severely injured a partner, including the fact that there are six nations in which 3% or more of the men severely injured a partner and four nations in which 3% or more of the women students severely injured a partner.

Summary and Conclusions

Although not all the correlations were statistically dependable, the general pattern is that nations where spanking is more prevalent tend to also be nations in which a higher percent of the students in this study approved of slapping a partner, actually physically assaulted a partner, and injured a partner. These societal-level results show that the link between spanking and violence applies not only to the characteristics of individual persons, but also to the national contexts in which the students in this study lived.

Limitations

Before drawing further conclusions from these results, some important limitations need to be mentioned. First the data is on university students and may be unique to that sector of the population of a nation. However, the results are consistent with those of other studies (including the preceding chapter), which have found similar relationships for representative samples. In addition, there is evidence that nationto-nation differences found for these students corresponds to national differences in the same variables found by other studies. Evidence showing the validity of the International Dating Violence Study data is in Straus (2009b ).

Another limitation is that about two thirds of the sample is female. We reduced the potential problems resulting from this limitation by conducting separate analyses for males and females.

The measure of spanking is another limitation because it is recall data. However, as we pointed out in a previous chapter, there is empirical evidence indicating that adult recall of events in childhood can provide a valid measure of childhood experiences (Coolidge et al., 2011; Fisher et al., 2011; Morris & Slocum, 201 0). Another limitation of the measure is that it asks about having been spanked or hit a lot. As explained in the description of this measure, we think the phrase a lot fits the experience of most children. Nevertheless, the number of times the students had in mind for a lot is unknown, and it likely varies between students and sites. In addition, because the question asked about being spanked or hit a lot, it could be interpreted as a measure of physical abuse. Our opinion, however, is that this is not likely because, as pointed out earlier, the research shows that two or more times a week is typical. As a consequence, one would have to conclude that physical abuse is typical. Our opinion is that any spanking of children is abuse, but that is not the cultural or statistical norm in the United States or most other nations.

Finally, although we controlled for the score of each nation on the limited disclosure scale, because of the small sample size (32), we did not control for enough other variables to have more confidence that the results really reflect the effect of spanking, such as whether there was violence between the parents. However, the study in the preceding chapter did control for violence between the parents and found that spanking made a unique and additional contribution to explaining the occurrence of assaulting a partner.

Links between Spanking and Assaulting Dating Partners

Keeping these limitations in mind, the results support the hypothesis that the larger the percentage of persons in a social context who were spanked, the higher the prevalence of three aspects of violence in partner relationships: cultural norms tolerating or supporting hitting a partner, physically assaulting a dating partner, and assaulting severe enough to injure a partner. An unexpected fmding is that the links between spanking and these three aspects of partner violence are stronger for women than for men. More than 200 other studies have found the percent of women who assault a partner is as high or higher than the percent of male partners who assault a partner (Archer, 2002; Desmarais et al., 2012). The results in this chapter on the stronger link between spanking and partner violence for women, when combined with the data showing high rates of spanking experienced by these women, may be part of the explanation for the high percentage of women who physically assaulted a partner.

Why Is Spanking Linked to Violence against a Partner?